Why the Celtic Cross?

The Lasting Legacy of Christian Missions to the British Isles

All analogies and illustrations about the doctrine of the Holy Trinity inevitably fail, mislead, or fall short. When someone begins with, “The Trinity is like…” or, “This story might help us understand the Trinity…” it’s wise to keep your Bible close. There’s an inherent danger of going off course. Many well-meaning attempts to explain the Trinity unintentionally distort Scripture, even though I don’t think these believers are heretics. Often, even in Christian communities that faithfully recite the Apostles’ Creed—or, more clearly, the Nicene Creed—teaching on the biblical doctrine of the Trinity is limited. So, what should we say? A prudent response might be, “As little as possible.” In other words, believe and affirm what Scripture reveals but don’t speculate beyond it. However, there remains the intellectual and spiritual tension that arises when contemplating the Trinity, and we will address that in due course.

The Doctrine of the Holy Trinity

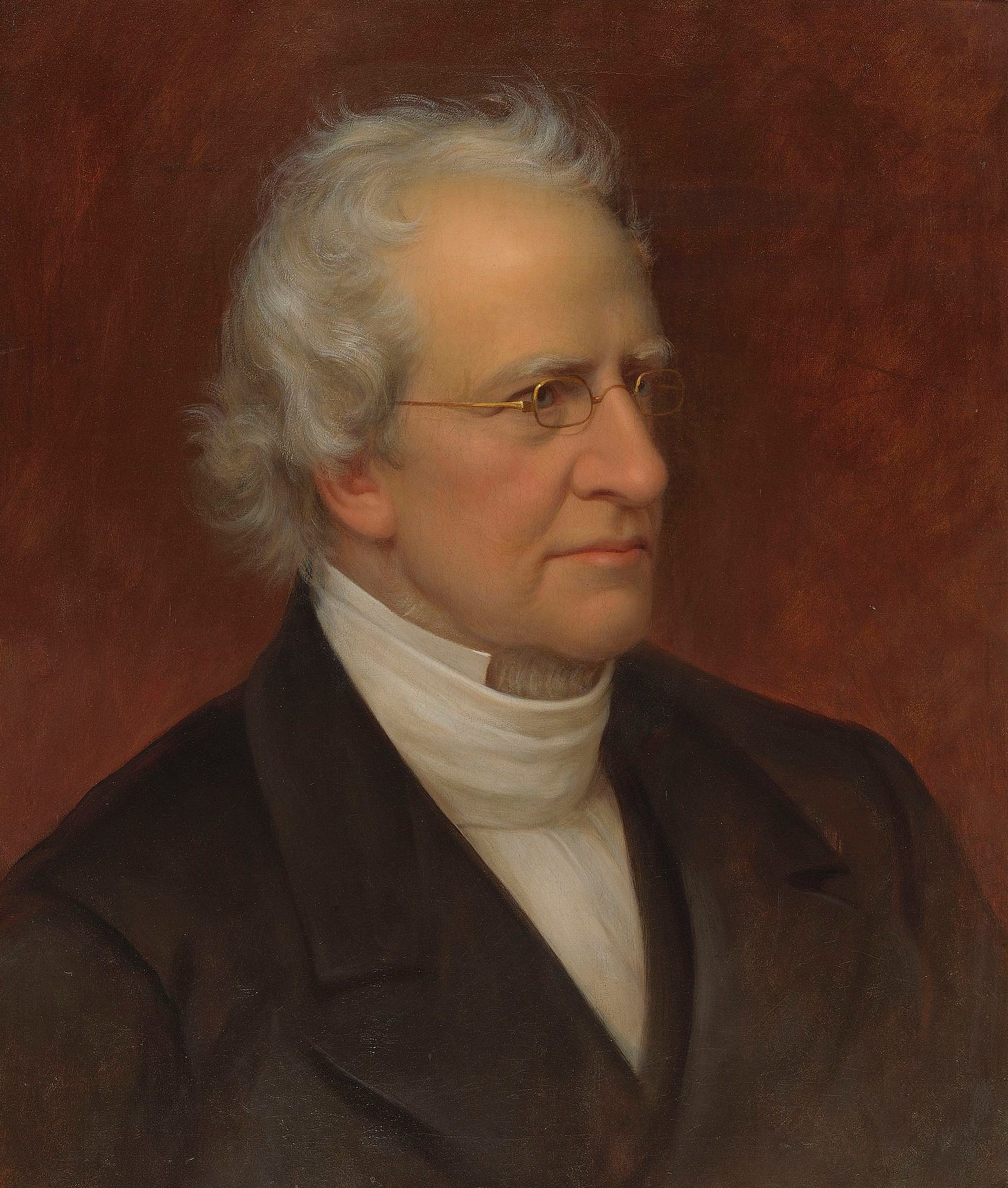

As B. B. Warfield of old Princeton urged, the Holy Trinity is a doctrine revealed in Scripture and through time.1 Warfield’s peer, the second principal of Princeton Theological Seminary, Charles Hodge (1797-1878), used the phrase “The progressive character of divine revelation” to describe how one perceives the self-identity of Almighty God.2 There is not a single doctrinal description of the Holy Trinity. Instead, as one reads through the Scriptures, one becomes aware that God is one, three in one. These Persons of the Godhead are not confused; they are not blended, and one Person of the One True God is not subordinate to another Person of the Godhead. The Westminister Confession of Faith expresses clarity in brevity:

In the unity of the Godhead there be three persons, of one substance, power, and eternity: God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Ghost: the Father is of none, neither begotten, nor proceeding; the Son is eternally begotten of the Father; the Holy Ghost eternally proceeding from the Father and the Son.—Westminster Confession of Faith, 2.3.

Accordingly, Charles Hodge wrote in his Systematic Theology,

To say that this doctrine [of the Holy Trinity] is incomprehensible is to say nothing more than must be admitted of any other great truth, whether of revelation or of science. To say that it is impossible that the one divine substance can subsist in three distinct persons is certainly unreasonable.3

Warfield describes the revelation of the Trinity God as a “solution” to the mystery that presents itself in our conception of the Almighty:

Difficult, therefore, as the idea of the Trinity in itself is, it does not come to us as an added burden upon our intelligence; it brings us rather the solution of the deepest and most persistent difficulties in our conception of God as infinite moral Being, and illuminates, enriches and elevates all our thought of God.4

God, and, thus, His self-revelation as Triune, is at once a mystery and a mystery unveiled. Yet, unveiling the Truth of the Trinity does not remove the human limitations in understanding the Trinity. The Holy Trinity is, as Hodge asserts, “incomprehensible.” We have no pure reference for the Holy Trinity. We have only the truth of the Word of God sustained by the Person of our resurrected and ascended Jesus. He testified to the One True God as triune. The rest of the biblical texts are sufficient unto themselves, but all these assertions are sealed with divine authority in Christ. The Word became flesh. The resurrection foretold by Jesus (and the prophets) and witnessed by many, over five hundred at one time (who could counter the testimony if not true), is the ultimate measure of inerrancy and infallibility for all other biblical assertions. Thus, we state the doctrine of the TrTrinityith with the words of Scripture. The doctrine is not a philosophical formula. It is a biblical proposition gathered from the unity of the many assertions in Scripture. If there are no precise references, there are “hints” to borrow an idea from C. S. Lewis (1898-1963).5 This leads us to the evangelist to the Picts, Columba.

Saint Columba and Iona

The Celtic cross is, more correctly, “Saint Martin’s cross” or “the Iona cross.” However, it will always be associated with “The Apostle to the Picts,” Columbia (521-597). Columba was an Irish minister who studied under the Welsh Christian community in Ireland. The seminary was founded by one of Saint David’s students from Pembrokeshire. Columba departed Ireland to evangelize Western Scotland. The area was not only home to the Picts but also to the Gallic-speaking peoples. In fact, Columba’s kinsman lived at Iona, and that might have helped the great missionary to establish his ministry there. While much of the evangelistic ministries of the first several hundred years of life after Christ are sometimes recorded at the nexus of legend and histories of those who were converted from paganism, the sparse facts may be trusted that this man Columba arrived and conducted a successful mission to Iona. He would later return to Ireland to establish an abbey there. Like David in Wales, Columba was very much what we would call a “church planter.” He established communities of believers who could, then, perpetuate a life in Christ as taught in the Holy Scriptures. Among other obstacles in evangelizing the Pictish peoples, Saint Columba must have faced the challenges of preaching the truth of the Trinity. Though he likely borrowed this from another, the evangelist established what we know as the Celtic cross, which stands today on the Isle of Iona (see the photograph at the beginning of this article). The Celtic cross bears witness to the Triunity of God by connecting the chancel (top extension) of the cross’ center column with the transept (the horizontal beam at the top of the center column; transept is “from Lat. trans, across, and septum, enclosure”) to create a one in three visual.6 Thus, the Celtic cross is associated with stating the truth of the Trinity without pretending to explain it. Over time, British Christians from all branches of the Church began to use the symbol in art and architecture to proclaim the One in Three, best understood at the cross.

The Celtic Cross is ancient but ever new; ordered but spontaneous; plain but artistic; quiet, yet speaking; respectful but joyful; mysterious but open; leaving our own place to help others find their true home; seeking to establish Something by the power of Someone more significant than the sum of ourselves; and finding ourselves by losing ourselves in a divine vision, which will endure throughout all generations. This cross helps all who enter the community to recalibrate faith and life in Jesus Christ, who paid for our sins on the cross.

“The Biblical Doctrine of the Trinity,” in The Works of Benjamin B. Warfield (10 vols). Grand Rapids: Baker, 1991), 2:133–72.

Charles Hodge, Systematic Theology, vol. 1 (Oak Harbor, WA: Logos Research Systems, Inc., 1997), 446.

Hodge, Systematic Theology, 445. I put emphasis on the words “incomprehensible” and “impossible.”

Warfield, Works, 135-139.

C. S. Lewis, “Mere Christianity,” in The Complete C. S. Lewis Signature Classics (London: HarperCollins, 2007), 175.

“Transept,” in Encyclopædia Britannica, 1911.