Why England Must Not Fall

England’s 0.62% Matters More Than You Think

There is a struggle in England today that mirrors the wider crisis of the secular age across Western civilization. Yet England’s struggle is uniquely urgent, for her historical influence on the world makes her decline more consequential than most. To grasp the stakes, one must first consider how small England’s population is compared to her outsized impact on civilization.

England today accounts for just 0.62% of the world’s population—a mere 57 million people out of more than eight billion (United Nations World Population Prospects 2024). On paper, that number seems insignificant. Yet England’s influence on law, liberty, and civilization is staggering. The current crisis there, marked by cultural amnesia and self-destructive policies, matters far beyond the shores of the British Isles.

A Disproportionate Legacy

Douglas Murray, reflecting on Israel’s struggle for survival after the Hamas attacks of October 7, 2023, observed that though Israel is only 0.2% of humanity, its loss would be irreplaceable. Its contributions in literature, law, and conscience are not measured by population but by significance (Murray, The War on the West, 2022). The same truth applies to England.

Thomas Sowell, in Race and Culture (1994), pointed out that the English, as an island people and a transatlantic bridge to North America, created a culture “rarely equaled and arguably never surpassed.” From parliamentary government to modern science, from Shakespeare to the King James Bible, the English bequeathed a patrimony that shaped nations across the world.

Yet today, England’s way of life is imperiled. Ideological “wokeism,” policies that enable illegal migration, and a growing hostility toward Christianity are eroding her very foundations.

What England Gave the World

At Runnymede in 1215, King John sealed Magna Carta, embedding biblical principles of covenant and justice into the law. This event birthed English common law—the legal system that would become the basis for constitutional government on multiple continents. It was, in many ways, the outworking of applied theology.

As historian Tom Holland demonstrates in Dominion: How the Christian Revolution Remade the World (2019), ideas we take for granted—human rights, freedom, even concern for the poor and the environment—did not emerge in a vacuum. They were nurtured by Christianity, often carried by the English-speaking peoples.

Consider also England’s model of Christian nationhood. Nationalism has been cast in a negative light in recent years, but in England it often meant liberty under law. Christian influence shaped civic life in such a way that even non-Christians found room for self‑expression. When rooted in Christ, national identity yielded tolerance, not tyranny.

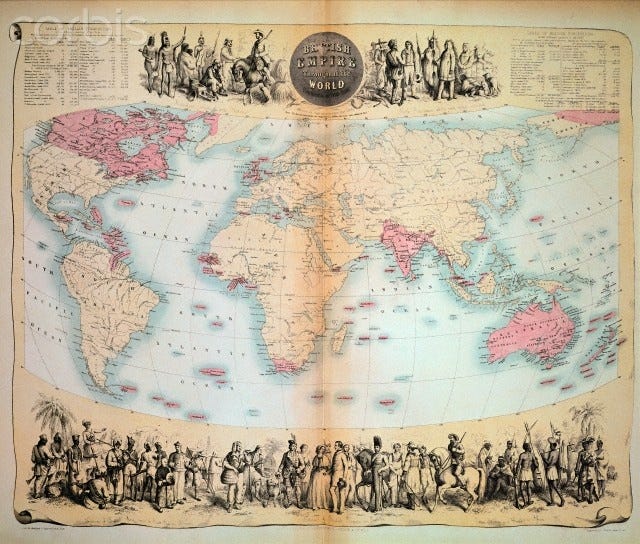

Even the British Empire, though not without flaws, bore marks of Christian benevolence. Missionary statesmen such as William Carey and David Livingstone represented an impulse to educate, to heal, and to govern justly. Unlike empires built solely on conquest, the English sought to leave behind schools, institutions, and enduring frameworks for human flourishing

What We Stand to Lose

If England succumbs to the forces of secular socialism and cultural dissolution, the loss will not be confined to her borders. The entire Anglosphere—comprising America, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and Ireland—rests on English foundations. Nations in Africa, the Caribbean, and Asia, touched by English governance, would also feel the collapse.

America, often described as an extension of the British experiment, still carries forward England’s legacy of ordered liberty. Yet America, too, is wrestling with many of the same destructive currents. If England falls, the tremor will be felt here.

A Call to Remember

History demonstrates that less than one percent of humanity has produced ideals that lifted countless millions. England’s legacy was rooted in Scripture, vindicated by the resurrection of Jesus Christ, and confirmed by natural law. The apostle Paul declared, “Where the Spirit of the Lord is, there is freedom” (2 Cor. 3:17). England, more than most nations, embodied this truth.

Today’s British leadership, under Prime Minister Keir Starmer (2024–), speaks the language of “human rights” but severs those rights from their biblical foundation. Without Christianity, human rights become abstractions easily manipulated by ideology.

That is why the present struggle in England is so important. To erase Christian Britain is not to move forward but to regress—to a pre-Christian world where might makes right, and liberty is the privilege of the powerful.

“The Glorious Revolution reminds us that lasting change comes not by force, but under the banner of Christ’s cross. Revival must precede renewal.” —Michael A. Milton

England’s 0.62%

England matters because her 0.62% has always mattered more than numbers suggest. She has been a light to the nations. To extinguish that light now would not only diminish England but darken the world.

The question is whether England will rise again—whether the people of that green and ancient land will remember who they are, and what they have given, not only to themselves but to us all. One of England’s greatest preacher-poets proclaimed from the pulpit of St. Paul’s:

“No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main. If a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe is the less… any man’s death diminishes me…” —John Donne, Meditation XVII, Devotions Upon Emergent Occasions (1624)

It is more than a “clod” being washed away. It is a civilization. For if England falls to an elitist socialism that has flooded that fair land with illegal immigrants and a resulting violence that is destroying the fabric of its very existence, then the world will feel the loss. And that loss shall be great.

Englishmen, Scotsmen, Welshmen, and Irishmen: the honor of your women and the safety of your children depend upon your response in this critical hour. Remember that the Glorious Revolution was not merely a political event but a transformation of self-governance achieved through strong yet peaceful means, under the banner of the cross of Christ. Do not look to the Bastille. That is not your heritage. Remember Wycliffe and Cranmer. Read Wilberforce and Wesley, John Newton, George Whitefield, and David Livingstone. Again and again, spiritual revival has breathed life into civic renewal. So it shall be now: only such power can bring forth wise resolutions and lasting transformation.

"Never was so much owed by so many to so few.” That has always been your story, your contribution to the world. And so, grateful descendants of the People of the British Isles, and the billions of spiritual heirs of English law and liberty around the world, look on with prayerful hope:

“And did those feet in ancient time,

Walk upon England’s mountains green:

And was the holy Lamb of God,

On England’s pleasant pastures seen!”1

“Englishmen, Scotsmen, Welshmen, Irishmen: the honor of your women and the safety of your children depend on your response in this critical hour.”—Michael A. Milton

References

John Donne, Meditation XVII, in Devotions Upon Emergent Occasions (1624).

Douglas Murray, The War on the West (New York: Harper, 2022).

Thomas Sowell, Race and Culture: A World View (New York: Basic Books, 1994).

Tom Holland, Dominion: How the Christian Revolution Remade the World (New York: Basic Books, 2019).

United Nations, World Population Prospects 2024.

The Holy Bible, English Standard Version (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2001).

An Officer’s Portrait, An Empire’s Story

In painting this fictional colonel of the Grenadier Guards, I sought to capture a generation that led men in battle and later carried that same discipline into the stewardship of the empire. Medals, crimson tunic, and sword—symbols of service—remind us of lives lived under duty and honor, echoing into our own search for faithfulness in vocation.

Such men, once commanders in the field, often became leaders in the civic and corporate spheres of the British Empire—embodying discipline, honor, and continuity in both military and civilian life. The painting reflects a transitional moment, where battlefield valor gave way to the stewardship of institutions across an expanding empire.

As Paul reminds us, “Moreover, it is required of stewards that they be found faithful” (1 Cor. 4:2 ESV).

William Blake wrote what would become one of England’s most beloved national anthems as an introduction to his work on John Milton. Blake did not believe that Jesus visited England or the British Isles in his flesh. He is pointing to both the early missions to Britain after the resurrection and, in particular, John Milton’s History of Britain. Milton repeats the stories about Joseph of Arimethea, acting as a tin merchant (and preaching in Britain after the resurrection). What is indisputable is Britain’s identity as a Christian people, so early after the resurrection of Jesus Christ and the continuing dominance of Christian teaching, ideals, and missionary zeal to the world.

For those interested in pursuing a self-study on the history of Christianity in the British Isles, I have prepared a recommended reading list that would serve as a comprehensive course. Here is a list divided chronologically. It is a substantial list, but it would make a meaningful long-term reading project. Allow yourself a couple of years. You will be amazed by the depth and breadth of Christianity in Britain. There is no other logical reason why the British people exercised so much influence in many areas of human endeavor, and why their culture influenced so many others positively.

[If I had to pick one? Go with Bray.]

I. Pre-Christian Background

Barry Cunliffe. Britain Begins. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Begin here for an archaeological and cultural foundation stretching from prehistory to the Roman period.Pliny the Elder. The Natural History, trans. John Bostock and H. T. Riley. London: Henry Bohn, 1855. Book 4.30. [Online edition]

Next, consult this Roman-era description of pre-Christian Britain.J. T. Koch. “New Thoughts on Albion, Iernē, and the Pretanic Isles (Part One).” Proceedings of the Harvard Celtic Colloquium, January 1986, 1–28.

Philological and cultural insights into early Celtic ethnonyms and identities.Anne Ross. Pagan Celtic Britain: Studies in Iconography and Tradition. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1967.

A classic study of the gods, symbols, and rituals of early Celtic religious life.Ronald Hutton. The Pagan Religions of the Ancient British Isles: Their Nature and Legacy. Oxford: Blackwell, 1991.

Modern reassessment that invites fresh interpretation of earlier paganism.Miranda Aldhouse‑Green. Exploring the World of the Druids. London: Thames & Hudson, 1997.

Finishes the section with a richly visual exploration of Druidic culture.

II. Classical and Medieval Sources

Bede. Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999 [orig. 731].

The authoritative early medieval narrative of England’s conversion to Christianity.John Milton. The History of Britain, ed. Graham Parry. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012 [orig. 1670].

A Puritan historian-theologian’s perspective—read alongside Bede for depth in interpretative tradition.

III. Overarching Modern Synthesis

Gerald Bray. The History of Christianity in Britain and Ireland: From the First Century to the Twenty‑First. Apollos (IVP), 2021.

A magisterial and evangelical-integrated synthesis pooling narratives from England, Scotland, Wales, and Ireland. Accessible for students and lay readers alike.

IV. Reformation & Protestant Identity

Patrick Collinson. The Religion of Protestants: The Church in English Society 1559–1625. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982.

Begin here to understand the theological and cultural forces that shaped Elizabethan Protestantism.Diarmaid MacCulloch. The Reformation: A History. New York: Viking Penguin, 2003.

A comprehensive, panoramic examination of the Reformation, placing England in a European context.Alec Ryrie. Being Protestant in Reformation Britain. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Evangelically attuned study of lived Protestant spirituality and identity.J. C. Ryle. Light from Old Times; or Protestant Facts and Men. London: Charles Murray, 1890.

Paired well with Ryrie—a Victorian evangelical celebration of Protestant heritage.Michael A. G. Haykin. The Reformers and Puritans as Spiritual Mentors. Dundas, ON: Joshua Press, 2012.

Capstone reading—applies the legacies of the Reformers and Puritans directly as pastoral resources.

V. Early Christianity in Insular England

Henry Mayr-Harting. The Coming of Christianity to Anglo-Saxon England. 3rd ed. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1991.

Scholarly classic on the missionary and institutional establishment of Christianity.Nicholas Higham and Martin J. Ryan. The Anglo-Saxon World. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013.

An expansive cultural and political backdrop for understanding church formation.Michelle P. Brown. The Lindisfarne Gospels: Society, Spirituality and the Scribe. London: British Library, 2003.

Concludes the study cohort with artistry, piety, and spiritual culture embodied in the Lindisfarne manuscript.

Hello Mike. I had sent you a note and a photo of some fabulous clouds that reminded me of you and John Constable. I wonder if that arrived or if there is a better address to reach you these days.

I talked to Darrell recently and he said he had a brief conversation with you. I like to keep in touch with him, he served us all so well in Hampton Place

Warm regards

Roger

Amen and amen. Thank you for this trenchant analysis.