As a pastor, few shepherding occupations rated higher than the weekly cry to the community to set apart time, place, heart, and mind for a Royal Waste of Time (1999), as Dr. Marva Dawn wrote of the corporate worship of Almighty God. In the Call to Worship, I would begin the service,” This is the Day the Lord has made. Let us rejoice and be glad in it. Hear the Call to Worship the Living God.” And then, we—People and Pastor—began a dialogical retelling of the Gospel in Reformed worship. At the heart of Christian worship is the mysterium tremendum, the “awe-inspiring mystery” of the finite and the infinite in unity—of the LORD God meeting with His people and those who would repent and believe.1 If John, the “disciple whom Jesus loved,” fell at the Lord’s feet as dead, how shall we approach the Friend of Sinners? My Friend I love is yet the Jehovah God of all, and I am but mortal, His creature. If I am aware of His presence, this is not my decision. Instead, I fall before him intuitively, instinctively. In corporate worship, He is made present by His Spirit through the means of grace, Word, Sacrament, and Prayer. Thus, the passage and the Geneva Bible’s concise commentary remind us of why worship is, for most of Judeo-Christian history, a supreme act of reverence (Hebrews 12:28-29):

And when I saw him, I fell at his feet as dead. {11} And he laid his right hand upon me, saying unto me, Fear not; {12} I am the first and the last:

“A religious fear, that goes before the calling of the saints, and their full confirmation to take on them the vocation of God” (The Geneva Bible Translation Notes [1599]).

O the beauty of the Savior, the Son of Man, touching His creature, and saying those familiar words that echo through Scripture, “Fear not.” With faithful response (worship must be in spirit and in truth, it is never a transactional event; it is of faith or it is hollow) to such an announcement, time and timelessness (T. S. Eliot) converge in sacred assembly:2

“Declare a holy fast; call a sacred assembly. Summon the elders and all who live in the land to the house of the LORD your God, and cry out to the LORD” (Joel 1:14, NIV).

In considering the concept of holy space, it becomes apparent that a theology of dwelling is central to the larger Judeo-Christian tradition and, with revelatory fulfillment, to the Christian Church. As Greg Beale taught us, the temple was a sign of God dwelling with us and a “cosmic” alert to the incarnation of Jesus Christ.3 Yet, the reality of God making a home with man does not negate the call, “Come unto me” (Matthew 11:28). For we must go up to the temple of God.

The prophet Joel declares in Joel 1:14,

“Declare a holy fast; call a sacred assembly. Summon the elders and all who live in the land to the house of the LORD your God, and cry out to the LORD.” Although we do not advocate the perpetuation of the Old Testament temple, the Bible offers continuity in spiritual application, also retaining the Biblical emphasis on “sacred space.”

We need not be mystical about speaking of sacred space or sacred time. We mean that physical place dedicated to God and for “sacred assembly,” i.e., Christian worship. The pagan notions of a duality of material and spirit (in which the former is evil, and the latter is good) are crushed beneath the wholistic vision and Creatorly concern for all things. Thus, we may speak of spiritual things within our Lebenswelt (German, “life-world,” i.e., our experiential world).4 We may also speak of “holy” as both the subject of mysterium tremendum (awe-full, ethereal, set apart, divine) and our human response to it (awe-inspiring, transformative).5

At the heart of Christian worship is the mysterium tremendum, the “awe-inspiring mystery” of the finite and the infinite in unity—of Almighty God meeting with His people and those who would repent and believe. — Michael A. Milton

The theology of the temple underscores God’s desire for a dwelling among His people. This abode of the invisible God was intended to exist within the city yet distinct from it. The architectural design of the meeting place between God and humanity reflects a proper theology: the eternal God’s self-revelation while remaining present with His people. An architectural historian termed this concinnitas—in which temple features are harmoniously interconnected, or, as Sir Roger Scruton defined it, an “apt correspondence of part to part, the ability of one detail to give a clear visual answer to the ‘why?’ posed by another.” ”6 As each part was integral to the whole in body, so it was in the soul of sacred space, the liturgy. Each liturgical movement answers the one before and anticipates the one after. Thus, the golden thread of the Gospel is united by the entrance, acknowledgment of God’s presence, proclamation of His word, remembrance of the covenant mediated by Christ’s sacrifice, and dismissal. In this way, the architecture of the material and the anatomy of the liturgy reveal the God we cannot see, the hidden God in His triune disclosure. The enigmatic revelation of God amidst His concealment is humanity’s salvation. God saves us by Body and Spirit, a real sacrifice of God’s limb and ligament, consciousness and pain, mediating a Covenant that is God’s idea that lingers from antediluvian days—sacred space-spiritual presence, lithic-liturgic, body-soul. Thus, our place and thoughts are set apart (by His invitation, not our initiative) and dedicated, consecrating a fixture in time and eternity. As Roger Scruton notes in The Soul of the World, temple stones witness the convergence of time and timelessness in sacred assembly: “The temple reveals God by concealing Him, and this paradox is symbolized in its structure and form.” ”7

In the early church, believers gathered primarily in homes from the New Testament era to the fourth century. Now more than ever, we need the elegy of sacred assembly, and even more “as we see the day approaching” (Hebrews 10:25, ESV). Philemon, a wealthy man mentioned in Paul’s letter, hosted such an assembly in his spacious home, possibly including a dedicated chapel for worship. Archaeological evidence supports this arrangement. However, the presence of house churches doesn’t negate the importance of a city temple, which became vital as apostles yielded to local pastors and house churches gave way to consecrated community meeting houses.

In the 21st century, the concept of holy space waned with the ascent of secularism, leading to blurred distinctions between sacred assemblies and other gatherings. Attempts to mimic secular venues eroded the unique nature of worship, and deconstructed liturgy led to the loss of holy space’s distinct purpose.

Although the full impact of secularism is yet to be explored, it’s evident that neglecting holy space hindered the church’s mission to bridge the gap between people and God. Conversely, cathedrals and churches in Britain and Europe suffered a similar fate, failing their mission due to diluted liturgy or abandonment, severing the connection between God’s message and physical space.

Attempts to mimic secular venues eroded the unique nature of worship, and deconstructed liturgy led to the loss of holy space’s distinct purpose. — Michael A. Milton

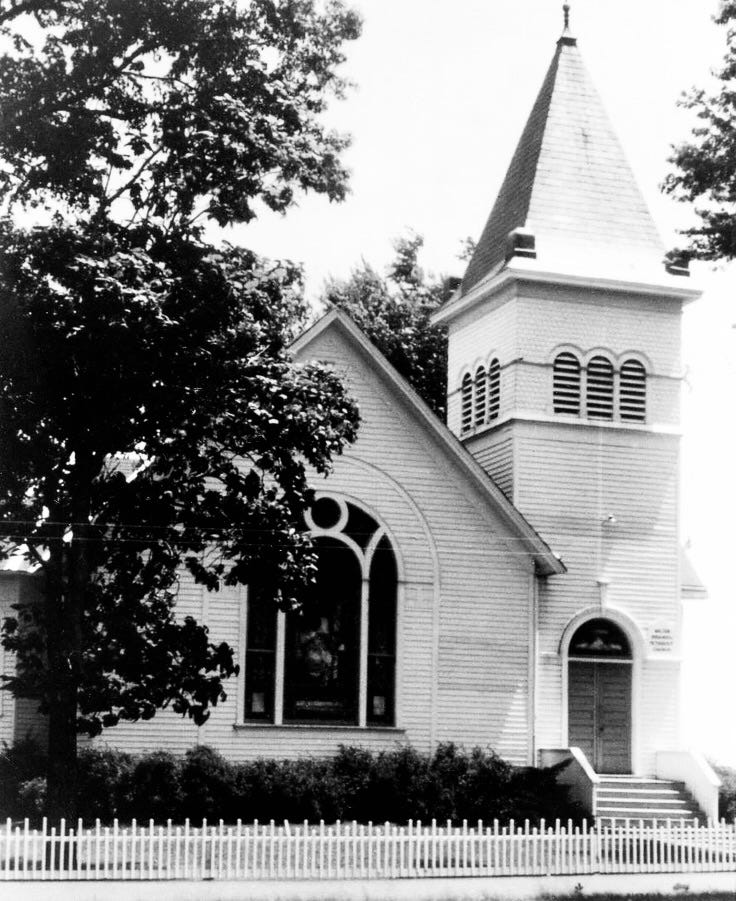

Both extremes can be reversed. The Huguenots in France worshipped in forests, carrying the pulpit from their dedicated house of worship, akin to Israel fleeing with the Ark of the Covenant. In doing so, these persecuted people of God revealed that sacred assembly could occur in unconventional settings through dedicated time and space based on Scripture. Sacredness resides not solely in grand cathedrals but in God’s presence and faithful proclamation of His word. This truth is evident in the architecture of Westminster Abbey in England or the simple design of a chapel in Iowa. Such biblical truth continues in New Covenant fulfillment as God dwells through the power of the Holy Spirit in the believer’s body, for the body is the temple of the Lord: “Or do you not know that your body is a temple of the Holy Spirit within you, whom you have from God? You are not your own, for you were bought with a price. So glorify God in your body” (1 Corinthians 6:19-20 ESV).

Sacred space and consecrated place are grounded in a theology of God with us and God in us through Jesus Christ our Lord in time and space, in seasons of the earth, and in the infinity of heaven. Both places merge in the divine service of worship. “The God who made the world and everything in it, being Lord of heaven and earth, does not live in temples made by man” (Acts 17:24).

As Christ continues to build His church, renewed attention to body and soul, edifice, and liturgy, will likely resurface. As Jesus promised in Matthew 16:18 (ESV), “I will build my church, and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it.” Whether we follow the cycle from house worship to community structures or restore cathedral ruins, a revival of pure religion concerning sacred time and space is imperative for the resurgence of sacred assembly.

Now more than ever, we need such a theology of Sacred Assembly—of the invisible God made visible by His word, of a place of worship that is in the community and yet apart from it, and a retelling of the gospel story in such a way that reverence and awe, wonder and beauty inspire us to make God the center of our lives, in liturgy and edifice, in other words: in body and soul. And we need this all the more “as we see the day approaching” (Hebrews 10:25, ESV).

We should reorient our practice, whether in a cave or cathedral, to this theological vision. For we are moving incontrovertibly to the denouement of this divine vision, as Revelation 21:3 affirms,

“And I heard a loud voice from the throne saying, ‘Behold, the dwelling place of God is with man. He will dwell with them, and they will be his people, and God himself will be with them as their God.’”

On that day, the Mysterium Tremendum is greater than ever before. For who could imagine such love? Yet, with the resurrection of Jesus Christ, Paradise Regained is underway.8 “Oh, sometimes it causes me to tremble, tremble, tremble.

Were you there when God raised him from the tomb?”9

For the phrase, Mysterium Tremendum, we are indebted to Rudolf Otto. The Idea of the Holy. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, 1970.

The Dry Salvages’, in The Poems of T. S. Eliot, vol. I: Collected and Uncollected Poems, ed. Christopher Ricks and Jim McCue. London 2015, p. 199. For a scholarly study on this sacred “intersection” that Eliot uses, see A J Nickerson, “T. S. Eliot and the Point of Intersection,” The Cambridge Quarterly 47, no. 4 (December 1, 2018): 343–59, https://doi.org/10.1093/camqtly/bfy017.

Greg K. Beale. The Temple and the Church’s Mission: A Biblical Theology of the Dwelling Place of God. United Kingdom: InterVarsity Press, 2014.

See Edmund Husserl. The Crisis of European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology: An Introduction to Phenomenological Philosophy. Germany: Northwestern University Press, 1970.

Otto. The Idea of the Holy.

R. Scruton, The Soul of the World. Princeton University Press, 2016, 124.

Scruton, 123.

John Milton, Paradise Regained (1671). D. Appleton & Company, 1854.

“Were You There?” African American Spiritual. Public Domain. See, e.g., the Psalter Hymnal: https://hymnary.org/media/fetch/96090.