Some Thoughts on the Reformation and Art

Common Grace for Good

Beauty beckons from the doorsteps of our imagination. The image of God, present in man but distorted by sin, nevertheless remains as the Sensus divinitatis, a vestigial witness to the great I AM. Repentance and faith in the crucified, resurrected, ascended, reigning, and soon-returning Christ are instruments to bring about justification before the Almighty. The Holy Spirit baptizes us into Christ (He is our head, we, His Body), resides within us, giving “union with Christ,” as we are adopted into the eternal family of God—true sons and daughters of God (and the spiritual promise to Abraham) saved and secured for eternity, solely on the atoning substitutionary sacrifice of our Lord Jesus.

Ecclesiastes 3:11 reminds us, “He hath made everything beautiful in his time: also he hath set the world in their heart so that no man can find out the work that God maketh from the beginning to the end.” The idea of seeking, finding, and celebrating beauty is embedded into the human spirit. Painting and drawing, along with other human creative expressions, are testaments to the divine nature of art.

The positive effects of the Reformation on art are often overlooked. We read of “the stripping of the altars” and the “surplice” fights (over English reforms in liturgical vestments) under Archbishop William Laud. And there were regrettable examples of overreaction and pure mischief (more Calvinist than Calvin, as they say). At this point, it is essential to remember Calvin’s perspective. John Calvin (1509-1564) did not wage a war on the arts. To the contrary, the great Reformer of Geneva called art a “gift.”1 Indeed, John Calvin’s theological vision of both the goodness of God to humanity and the sacredness of vocation, including art, rallied a new force of creativity.

Yet, artists like Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640) composed and painted with a Reformation worldview. As Tom Holland demonstrated in his book Dominion, even modernity and post-modernity find their meaning only in comparison with a Christian worldview, so also, art movements are defined by the ethos released during the Reformation. There is, of course, a continuum along the spectrum of the Reformation worldview. The Lutheran View and several other continental Calvinistic reformed views did not, and do not, see the artistic expression of, for example, Jesus on the cross as a violation of the second commandment. English Puritanism and some other expressions of reformed thought, e.g., Dutch Reformed, are either uncomfortable or prohibitive in their response to representations of the second person of the Trinity. Largely, English-speaking Presbyterianism is aligned with most of the Protestant praxis, namely, linear drawings or paintings of Jesus and his earthly ministry or historical representations, and not to be adored.

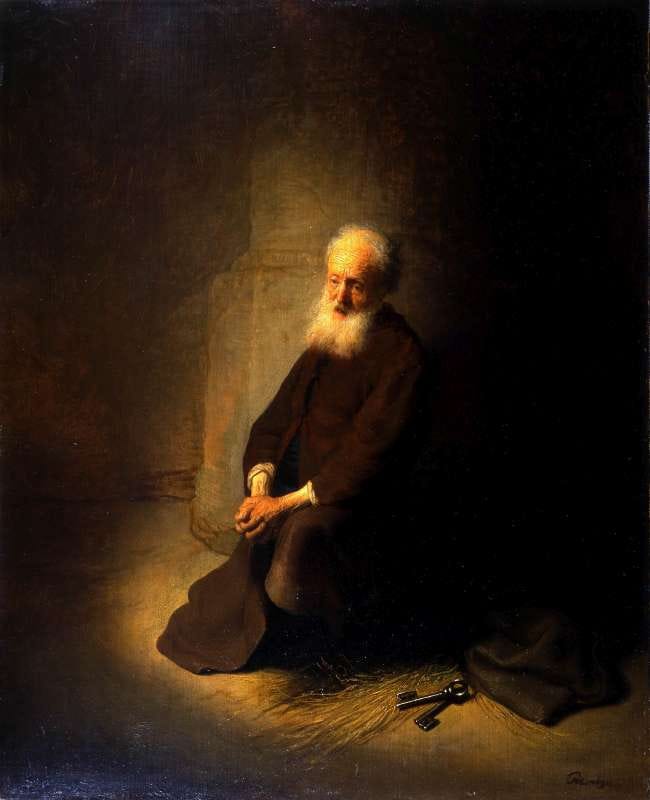

Similarly, most Protestant movements in English-speaking Christianity appreciate, for example, the work of Rembrandt (1606-1669) as he depicted the crucifixion but would disapprove of a crucifix on a communion table. This might seem inconsistent to some High-Church Anglicans or Roman Catholics. Still, the Reformation ethos supporting such decisions would be that one is historical and pedagogical while the other—a crucifix—is doxological and, therefore, prohibitive.

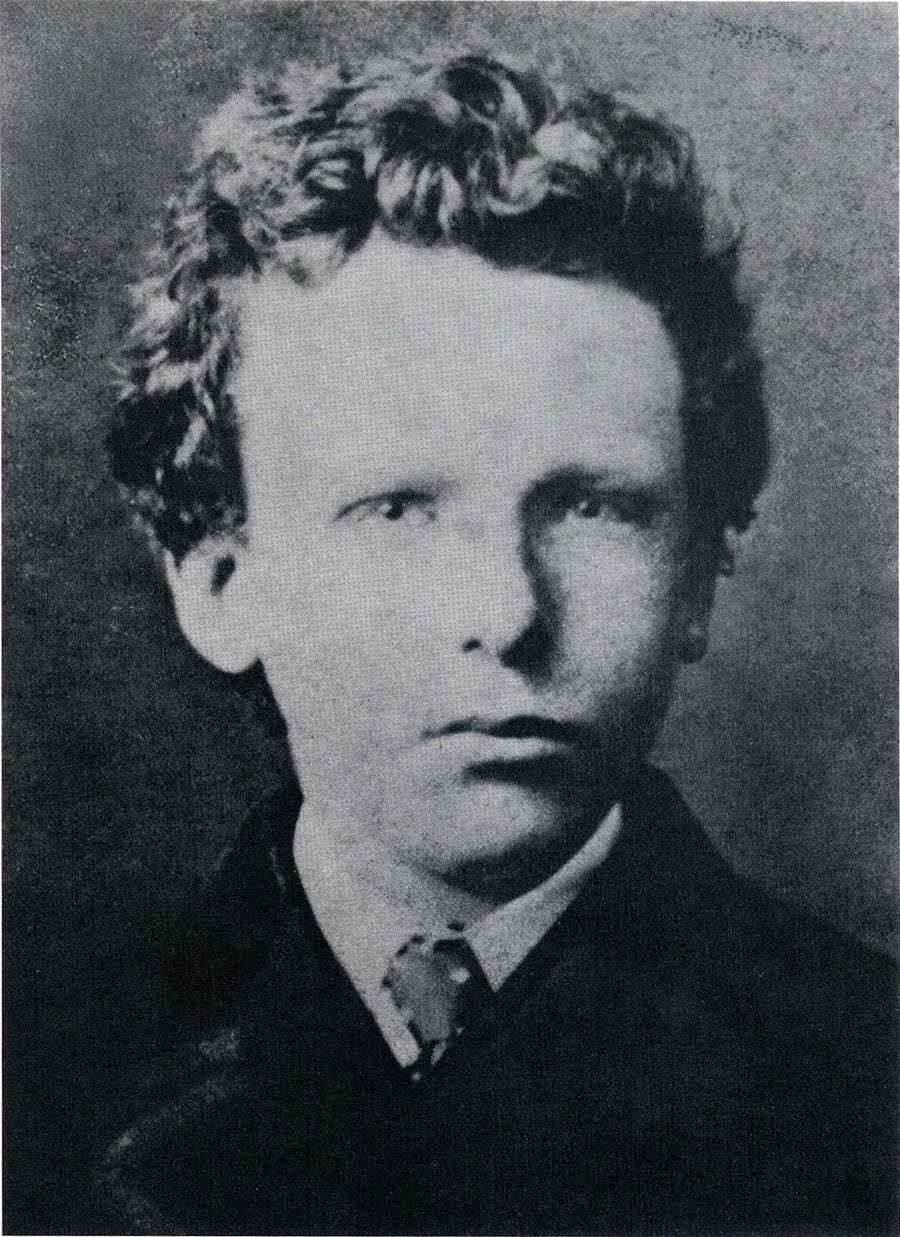

It is imperative to acknowledge that the Reformation wielded a profound influence over the realm of art, extending well beyond theological debates. This transformative movement not only unleashed creative impulses but also exercised judicious restraint. Undoubtedly, the Reformation left an enduring imprint on various facets of artistic expression, including composition, tonality, perspective, color, and dimension. Consequently, it assumed a pivotal role in shaping the trajectory of art history (in future essays, I intend to reflect further on this subject). It is enough for now to affirm what is so often missing in such discussions, viz., that the Protestant Reformation impacted artists such as Rubens, Rembrandt, and later luminaries like J.M.W. Turner (1775-1851), John Constable (1776-1837), Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890), Claude Monet (1840-1926), John Singer Sargent (1856-1925), and many others.

The author Mark Ford opined about why the Reformation created Vincent van Gogh: “By seeking to put Bibles into the hands of ordinary people and eventually have the Bible translated into English, the reformists were providing an extraordinary tool for individual liberty and creativity.” ”2 That is one facet of the Reformation that is most certainly present in the artistic endeavors that followed. I suggest another.

The Reformation centered on the doctrine of God’s grace. God’s grace is expressed in saving (“special”) and general ways. These general ways are for Abraham Kuyper (1837-1920) “common grace.” Perhaps, no one since Calvin articulated the reality of this divine truth at work in the world. In his Stone Lectures at Princeton, Kuyper said,

“And for our relation to the world: the recognition that in the whole world the curse is restrained by grace, that the life of the world is to be honored in its independence, and that we must, in every domain, discover the treasures and develop the potencies hidden by God in nature and in human life.”3

This grace is not a saving grace but a restraining grace that allows some vestigial beauty of Eden to remain (just as the Imago Dei is still present in the human being despite the Fall).

“In Lectures on Calvinism, Kuyper elaborates more the function of common grace as follows, ‘maintaining the life of the world, relaxes the curse which rest upon it, arrests its process of corruption, and thus allow the untrammeled development of our life in which to glorify Himself as Creator.’”4

Kuyper taught that we must not divine Common Grace and Special Grace. Where special grace is received (e.g., the Reformation), common grace follows (and Kuyper mentions the “flourishing” of the arts as an example). Thus, if a father receives Christ in a home of unbelievers, it will go better for the family. As the Lord sanctifies the man through Word, Sacrament, and Prayer, life only improves for others in the household. Common grace does not save but allows us to enjoy the beauty of God’s creation “east of Eden.” However, Common Grace can work as a prevenient influence in Saving Grace. In our example, the household is influenced not only by the man as husband and father (providing a federal headship that brings the wife and children and even household servants under the influence of the Gospel) but by the blessings that follow conversion. In this way, Common Grace acts as a kind of quiet evangelist but an evangelist, nonetheless. One asks, “Where do such blessings come from?” The father answers, “My newfound dedication to my work, to providing for my family, to loving our neighbor comes from my life in Christ, the resurrected and reigning Savior of my life.”

So, then, common grace allowed the post-Reformation artist to appreciate and develop creative responses to otherwise secular subjects. Liberated from the extremes of Erastianism and clericalism and unbending to the Renaissance or the Enlightenment, artists could see the world as physical and metaphysical.

The Reformation exalted the holiness of work. This is reflected in visual arts, e.g., the subject matter. The Reformed worldview allowed artists to seek and express the glory of God in landscape as well as in biblical motifs. Some might find it difficult to suppose that modern art owes its liberties to Martin Luther, but there is evidence to suggest just that. Undoubtedly, impressionism owes a debt to the Reformation. Impressionistic art is, at its heart, a metaphysical movement. The providence of ownership of The Fighting Temeraire (1839) by J. M. W. Turner is traced to a worldview that is at once tangible and atmospheric. There is no false dichotomy between spirit and matter. And this thought leads to just a few attributes of the relationship between Reformation and art:

The Reformation highlighted the relationship of creation with man.

The Reformation stressed the exposition of Scripture that transcended received tradition, seen in the visual arts, by allowing the artist to explore emotion in the subject matter. This is true whether it is John Constable’s cloud studies or Vincent van Gogh’s charcoal of an elderly woman.

The Reformation uncovered a theological truth of spirit and matter that liberated artists to explore both in their subjects. This may be the most significant difference between the Reformation’s influence on art and the Renaissance. The former celebrated God as the author of Good and Beauty and the Sender of Jesus Christ to redeem that diminished or distorted by the Fall. The latter believed that freedom of expression could be enjoyed without God or a critical worldview of systems and things. This is not to say that the artist painting with the impulses of the French Revolution is less proficient (skilled, insightful, or producing finer visual art) than one working out of, e.g., a Dutch Calvinist worldview. It does mean that they see things differently, and one might argue clearly. Clear-eyed observation may sound like a stretch for artists who size up their subjects by squinting their eyes, blurring their view to capture a spiritual presence. But such a method does not obscure the subject but instead seeks a technique to see and see through it. To see through the subject is to recognize the invisible powers at work in or through the subject. In a word, it is to admit that there is more than the eye can see.

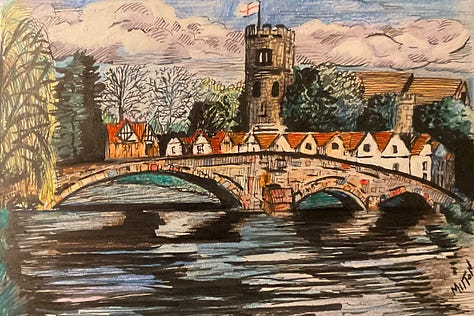

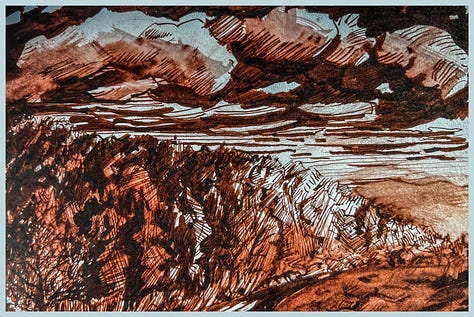

I am sharing some recent art that I created. In no way am I suggesting that what I have done is the example of my essay. I would point to Constable Turner and van Gogh for that. These are just pictures to share.5

Let us pray.

Our Father, Thou who has made all things good and by Thy Son has drawn our eyes to the beauty of the fields, grant, we pray, that we may grow in our love for Thee, in our appreciation of the common grace of life, and, especially the arts; so that we give Thee glory and praise, and that, by Thy mercy, some may come to Thee by faith; through Jesus Christ our Lord who lives and reigns with Thee O Father and the Holy Spirit, now and forever more. Amen.

Abraham Kuyper, Lectures on Calvinism [1898] (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1999), 87.

Mark Ford, “Van Gogh and the Protestant Reformation,” August 28, 2012, https://www.markford.net/2012/08/28/van-gogh-and-the-protestant-reformation/.

Abraham Kuyper, Lectures on Calvinism, 31.

Surya Harefa, “Common Grace and Hermeneutics: Utilizing Abraham Kuyper’s Common Grace for Facing Changes in Hermeneutics,” VERBUM CHRISTI: JURNAL TEOLOGI REFORMED INJILI 8 (January 26, 2022), https://doi.org/10.51688/VC8.1.2021.art3. The author is quoting from Kuyper's Lectures on Calvinism, 30.

If the reader desires more examples from my online portfolio, he could visit https://www.artpal.com/mamilton.