Gradually and Suddenly

Becoming the Preacher as Poet Declaring Theology as Wonder

A new semester is upon us. Thus, I share this pastoral letter. This is a letter to my students. I share it here because I believe it is suitable for the people of God to know the issues that Christian shepherds, counselors, teachers, chaplains, and fledgling pastors must address. While the matter taken up in this little note might seem small to some, it is about nothing less than delivering the word of the living God to people in this life. I warmly invite you to “listen in,” as it were. It may be that you find something for your soul.

To My Students on the (Under) Shepherd’s Voice

I have read that where there is beauty, there is a poet. I assert that where there is wonder, there is the preacher. However, too often, the preacher fails to discover wonder and marvel at the glory of its mystery from the Creator’s hand. Instead, he assumes the posture of an engineer. He doesn’t invite others to unveil the wonder but prefers, or feels obligated, to describe it. In doing so, he unwittingly strips the wonder away, rendering something beautiful plain. A poet strolling through autumn woods is captivated by the quilted colors of elm, birch, beechwood, sourwood, white oak, and persimmon. He reaches towards a dogwood branch, holds a leaf in his hand, and looks upon it for the first time as if it appears new with each encounter. He describes it as a vestige of summer, rusting and crumbling at its edges, too brittle to stay attached to the branch, yet not decayed enough to fall.1

A preacher might take the same walk, observe the same trees, and, if particularly curious, hold the same leaf. Yet, he describes the leaf in science or engineering language: “This is what a leaf looks like in the fall.” If he delves deeper, he might add, “Notice how the seasons are changing.” However, such evident and elementary figures of speech reveal a disappointing dullness of soul, if not a deprivation of spirit. This should not be the case. If the poet can look upon an autumn leaf with awe, why can’t the preacher see through the beauty of the familiar to articulate the wonder of the eternal? For the poet sees, but the preacher knows.

Nevertheless, the people he addresses cannot bypass the leaf to grasp the theological truth about spiritual metamorphosis without first encountering the leaf. Poetry and prose serve the preacher to highlight and focus on the object. The deeper theological truths that save and sanctify are revealed to the listener as she learns to appreciate the miracle of the leaf. Therefore, preachers must not bypass poetry to hasten the lesson. In doing so, we risk leaving our listeners with either poetry devoid of providence or ushering them into the realm of eternal verities without wonder.

Thus, let us embrace the poet’s art. In a vocation dominated by philosophical jargon, we would be wise to cultivate the art of observation and description. In The Sun Also Rises, Ernest Hemingway (1899-1961), whose writing style was shaped by terse sentence structures acquired as a reporter at The Kansas City Star, wrote through one of his characters that dreadful things happen “gradually and then suddenly.”2 This phrase captures a profound truth. I believe it can also be applied positively. We need not assume that next Sunday, we will step into the pulpit as a fully-fledged John Donne or Gerard Manley Hopkins (1844–1889), opening our sermon with the line, “The world is charged with the grandeur of God.” Instead, think, “Gradually and suddenly.” Suggest wonder before fully revealing it. Guide and shepherd the flock along the precarious paths of this present evil age, reminding them of the blessing of a narrow path beside a perilous, shoulderless road leading to dire destruction. Then, reveal the truth with the immortal insight granted to mortal man, a seeing man in a shadowy world becoming a blind man with a newfound vision. Thus, John Milton (1608-1674):

“When I consider how my light is spent, Ere half my days in this dark world and wide.”3

It is even more peculiar that we feel compelled to describe Biblical truth with the language of science rather than the rhythmic verse of prose, especially considering that our Lord Jesus Christ excelled beyond all human measure in causing his listeners to marvel at deep and wondrous truths of God through the similitude of the familiar sights of Men:

“The wind bloweth where it listeth, and thou hearest the sound thereof, but canst not tell whence it cometh, and whither it goeth: so is every one that is born of the Spirit” (John 3:8 KJV).

“And why take ye thought for raiment? Consider the lilies of the field, how they grow; they toil not, neither do they spin” (Matthew 6:28).

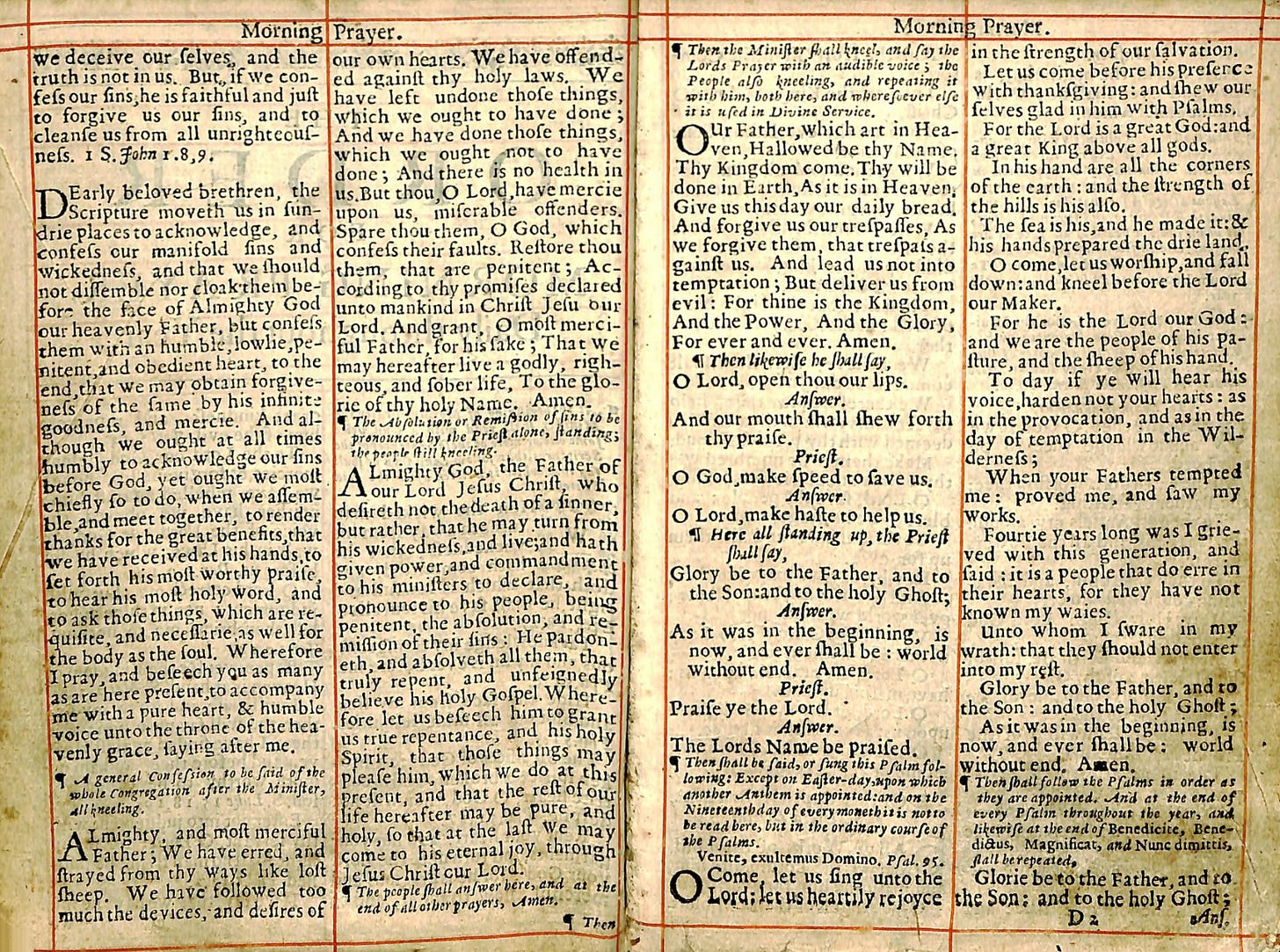

If one argues, “Yes, our Lord used such language to teach, but Saint Paul and St. John preferred the didactic,” it is true. Yet, the didactic content of their epistles was enhanced by stories, and the stories were made more comprehensible by metaphors. The farmer, the soldier, and the athlete were familiar figures in daily life. I am not recommending replacing the exposition of the living Word of God; instead, I am addressing the language in which we expound the truth. I advocate reading great preachers like James Stewart of Scotland, J.C. Ryle of Liverpool, George Whitefield, or even the English Puritans and Dutch experientialists, paying close attention to how they presented the text.

“Gradually and suddenly,” we will come to hold the leaf in our hands, observe its rusting, crumbling edges, and respond, “Is this not a recurring message from Heaven? The seasons may change, but all seasons of life are filled with His mercies and grace?” For we preach not only on the shoulders of theological giants but out of the spirits of biblical poets:

“. . . God hath made no decree to distinguish the seasons of His mercies; in paradise, the fruits were ripe the first minute, and in heaven, it is always Autumn, His mercies are ever in their maturity… He brought light out of darkness, not out of a lesser light; He can bring thy Summer out of Winter, though thou have no Spring; though in the ways of fortune, or understanding, or conscience, thou have been benighted till now, wintered and frozen, clouded and eclipsed, damped and benumbed, smothered and stupefied till now, now God comes to thee, not as in the dawning of the day, not as in the bud of the spring, but as the Sun at noon to illustrate all shadows, as the sheaves in harvest, to fill all penuries, all occasions invite His mercies, and all times are His seasons” (John Donne, Sermon, Christmas Day, 1624).

In embracing this approach, we align ourselves with the sensitive spirits of wise shepherds and connect to the very heart of Scripture’s narrative. The Bible is rich in imagery, metaphor, and beauty, engaging the mind and the soul in tasting Divine truth, the choice wine of resonant wonder. So let our “voices” be that of shepherds singing beneath the starry night sky where the dust of a hard day’s sojourning mingles with the enchanting smoke from a good fire, and the hills sing a little hymn of praise beneath a dazzling Milky Way. This is where sermons are sung to quieten the lambs of the Master.

I am indebted to the poem by Maggie Smith, “First Fall.” In that delightful poem, Smith writes of “the leaves rusting and crisping.” I also want to acknowledge the forward by Nikita Gill to The Wonder of Small Things: Poems of Peace and Renewal, edited by James Cruise (North Adams, MA: Storey Publishing, 2023).

Hemingway, Ernest. The Sun Also Rises. United Kingdom: Scribner, 1926, 141.

John Milton, “Sonnet 19: When I Consider How My Light Is Spent,” Poetry Foundation, January 16, 2024, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44750/sonnet-19-when-i-consider-how-my-light-is-spent.