A Theology of Learning

From Critical Thinking to Personal Transformation

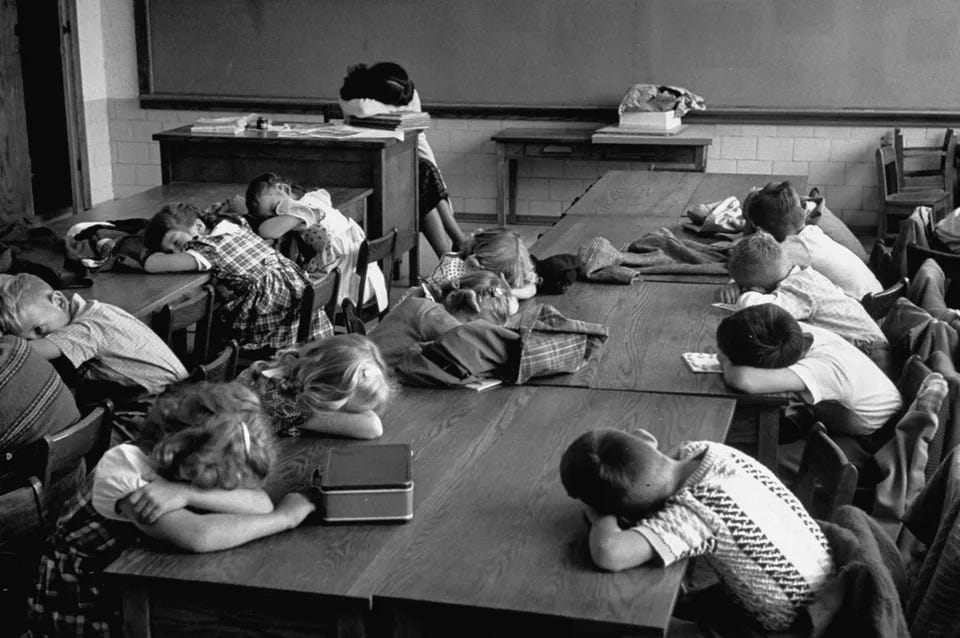

We should not be surprised if an ever-increasing deluge of information drowns our children in boredom.

This thought crossed my mind as I read a memoir recently, where a good and loving but overwhelmed mother—a single mother from rural America—returned home after the late shift of her second job. Barely standing from exhaustion, she scanned the room for her children. Her son and daughter, about ten and twelve years old, were right in front of her on a second-hand olive-colored sofa, their heads buried in iPads, courtesy of the public school’s “Every Child Online” campaign. The sounds of tanks, missile launchers, bells, and whistles emanating from the tablets shattered any pretense of study or homework.

Frozen in her tracks, the mother—exasperated beyond words—pulled the pin: Boom! “Get off those stupid computers!” Her outburst was no match for the lure of the games. Silence. The children didn’t even flinch. She hurled her red faux leather clutch toward the couch, where it landed between the two unmoved figures. “Hiya, Mom,” her daughter muttered, barely acknowledging her, oblivious to the Cat 5 hurricane that had just swept through the room. Undeterred, the mother snatched the iPads from their hands and demanded attention. “You will not sit around here with your heads in those #@$%^&/8! machines while I’m out trying to provide for you!”

After a sharp, unwise but understandable reference to a “deadbeat dad,” she laid down the law: “Get up from there right now and go watch cartoons! No more machines! Got it? Cartoons or nothing!”

Yikes. Well, my heart went out to her. It might seem absurd to think that trading one form of mindless entertainment for another would help, but she was at her wit’s end. One might even argue that—depending on the game—the interactive experience of the electronic medium would be preferred over the passive viewing of Tom and Jerry. But who could blame her for her response? She gets no help from their father, and if “it takes a village,” she gets nada from any such helpful hamlet. Our societal problem is like a glioblastoma, growing insidiously into the cognitive fabric of our lives, making it difficult to discern where the harm begins and ends. The flood of information and distractions has submerged a vital element of life: curiosity.

The English MP and public intellectual Edmund Burke (1729-1797) wrote, “The first and the simplest emotion which we discover in the human mind is Curiosity.”1 Curiosity arises when (as author Ian Leslie put it in his book Curiosity) there is “a gap” in understanding, prompting exploration to fill that gap. We all know what killed the proverbial cat. Nevertheless, curiosity in the mind of the English physician and scientist Edward Jenner (1749-1823) also led to a cure for smallpox. So, curiosity is dangerous (see the cat), and yet, it is the spark that ignites a fire to keep us warm, give us light, and cook our supper. And heals us.

Ian Leslie wrote that “Curiosity is vulnerable to benign neglect.” True. And don’t we know it? In this age of an unending flow of information, the creative impulse might just be numbed. Curiosity thrives in the space between knowing and not knowing—in the tension of mystery. It’s much like the paradox in physics, where light exists as both a wave and a particle despite the apparent impossibility of these two states coexisting. Yet they do. This gap—this mystery—is where deep learning begins, and theology offers us a starting point for intellectual curiosity. Ambiguity, the awareness of the gap, creates the self-generative motivation to know. Theology, literally, the study of God, gives us the existential framework to think.

The Good News of the Gospel of Jesus Christ, according to the Holy Bible, not only saves the soul but also offers healing for life itself. If we diagnose today’s cultural malaise, we see what Charles Taylor describes as “excarnation”—the separation of thought from lived reality, the denial of embodiment. To reject Christ and the teachings of the Bible is an act of extreme self-harm. Without the doctrines of Scripture, our humanity is exposed to the radioactive fallout of the post-Edenic world. We’ve inundated ourselves with so much information and so many portals to distraction that we’ve practically extinguished curiosity—the curiosity that once led Isaac Newton to discoveries that changed the world.

What if, instead of stifling curiosity with devices, we fostered it through stories, through theology, through the great truths of God? The real issue is not the iPads or the cartoons but the failure to teach children biblical truth through narrative. You know: Bible stories. Theology should be the foundation of learning—not just for children, but for all of us.

Curiosity, when rooted in a theological framework, becomes a powerful motivator for deep learning—the kind of learning that transforms. This type of education, grounded in a love for God’s truth, moves beyond shallow fact-gathering into something that renews the heart and mind.

The Holiness of Deep Learning

In the age of information, where knowledge is readily available yet often superficially understood, we face a crucial choice: to engage in mere linear learning or to commit to transformative, deep learning. Linear learning, grounded in transactional observation, may fill our minds with facts and information. However, when disconnected from the deeper realities of existence, it results in rote memorization—facts without purpose. This type of learning, though temporarily useful for academic recall, is often irrelevant to real life and is thus quickly forgotten. Rote learning—homogenized transactional learning devoid of worldview context and personal application—leaves us empty, causing any spiritual and intellectual benefits to be lost in the void. Yet, rote learning has its place. For instance, a medical student must memorize the names, functions, and pathologies of the twelve cranial nerves. Understanding these facts is crucial. My point, and my appeal to educators, is to frame such information within a relational context. How does CN VI (Abducens) relate to the other cranial nerves? To the rest of the body? To the individual?

At the heart of this distinction is how we approach truth. In a worldview anchored in the Holy Trinity, learning is not merely about acquiring facts but about participating in divine revelation. Truth is not transactional; it is relational. Thus, the Westminster Shorter Catechism,

“There are three persons in the Godhead; the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost; and these three are one God, the same in substance, equal in power and glory” (Q&A 5).

God is one. Yet, He is also three in one—a mystery that defines His essence as the Holy Trinity. As beings created in His image, we must ponder the profound significance of this divine revelation. What does it mean for our understanding of ourselves that God, in His triunity, has made us in His likeness? If knowing God is intrinsically tied to knowing oneself, how is His triune nature reflected in our humanity? When we fail to engage with this fundamental aspect of our being, what vital elements of our existence are lost? To embrace our full humanity, we must know how the divine triune relationship illuminates and enriches our own lives. To ignore this question is to live a life devoid of deeper meaning. But who truly takes the time to study God in order to gain a deeper understanding of oneself?

It is not coincidence that Augustine (AD 354-430) began his Confessions by tracing the mysterious but plain providence of God. The man of God, awe-struck by the grace of a triune God, wants to know God in order to know himself. God is not merely an unseen celestial Director suspended in the dark unknowable cosmos, He is the Creator, Sustainer, the way, the truth, and the life; the only fixed and unmovable variable—the uncreated and inextinguishable Light—in the changing river of time:

Great art thou, O Lord, and greatly to be praised; great is thy power, and infinite is thy wisdom.” And man desires to praise thee, for he is a part of thy creation; he bears his mortality about with him and carries the evidence of his sin and the proof that thou dost resist the proud. Still he desires to praise thee, this man who is only a small part of thy creation. Thou hast prompted him, that he should delight to praise thee, for thou hast made us for thyself and restless is our heart until it comes to rest in thee.2

God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Spirit are One. Eternally existing in mysterious triune glory, our Creator, Redeemer, and Comforter brings meaning to life and brings life to learning. The doctrine of the Trinity is essential to the intellectual life of human beings: Truth is eternal (John 14:6), communal (Matthew 28:19), and personal, reaching into the depths of our being to transform us (2 Corinthians 5:17). When learning is grounded in this Trinitarian framework, it reflects God’s own nature—Truth in relationship, community, and personal transformation.

Transactional learning absent of worldview context and personal application leaves us empty so that whatever nutrients were present in the learning are lost in the longing.—Michael A. Milton

Higher-Order Thinking: The Path to Deep Learning

Higher-order thinking, or critical thinking, often described as the ability to analyze, evaluate, and create, takes on a more profound significance for the Christian. It asks not only about the utility of knowledge but about its ultimate meaning. It moves from “What is this idea?” to “How does this reflect God’s truth?” and “What role does this idea play in God’s created order?” We might ask, “Where is God in all of this?” In engaging with this process, we begin to see the connection between knowledge and wisdom.

Critical questions arise: How important is this truth to me? How does God’s presence inform this? Where is He in this knowledge, and how does it draw me closer to His eternal truth?

Thomas Aquinas reminds us that “the things we love tell us what we are.” Learning, when rooted in a love for God’s eternal truths, becomes more than a mental exercise—it becomes worship. In Summa Theologica, Aquinas reflects on divine truth, noting that “The intellectual soul has an inclination to the truth, and this inclination is from God.” Learning, then, is not neutral; it can lead us toward God if approached with reverence and intentionality.

Learning in Relationship: The Process of Transformation

Deep learning moves us from isolated facts to integrated knowledge. This shift happens when learning takes on personal relevance. It is one thing to memorize facts about God; it is another to experience His truths in ways that transform our hearts and minds.

John Calvin speaks of the sensus divinitatis—the sense of the divine implanted in every human soul. This awareness of God draws us toward deep learning, urging us to move beyond superficial knowledge and into the divine. Calvin writes, “There is within the human mind, and indeed by natural instinct, an awareness of divinity.” This divine awareness compels us to engage with learning in a way that connects with our very souls. When we experience learning through the lens of the Holy Trinity, it ceases to be abstract and becomes deeply personal.

At this point, learning becomes a holy pursuit. It is no longer about what we know but who we are becoming in the process. The integration of God’s truth into our lives—our relationships, our work, and our personal development—ushers us into the fullness of our humanity.

The Search for Meaning

Walker Percy captures the essence of this holy learning in his work The Moviegoer:

“The search is what anyone would undertake if he were not sunk in the everydayness of his own life. To become aware of the possibility of the search is to be onto something. Not to be onto something is to be in despair.”

This search, this quest for divine truth, moves us beyond linear learning and into the transformative power of deep learning.

When learning is rooted in the divine—when we seek not just to know but to be known by God—we are no longer stuck in the mundane. The Holy Spirit guides us in our search for truth, and this search transforms us from within. The result is not just knowledge but wisdom, not just information but formation. In this way, learning becomes an act of discipleship, making us more fully human as we engage with the world in light of God’s eternal truth.

The Return of Curiosity Through Biblical Story

As I reflect on the image of the tired mother battling distractions for her children’s attention, I imagine a different scene. What if her cries for attention were answered not with mindless distraction but with curiosity ignited by stories of eternal significance?

Imagine this mother returning home to find her children, not lost in the glow of their iPads but engrossed in the Word of God. Like the fabled Dutch farmers reading the Heidelberg Catechism with their ploughman’s lunch, the children’s eyes, wide with wonder, ask, “Mom, what does it mean that God spoke through a burning bush?” “Mom, why can’t we see God?” “Mom, why did Jesus walk on water? And why can’t I walk on the water? I bet you can!”

Okay, okay: that might not happen immediately. The children will likely still play games and watch cartoons. But what if revival came? Or what if revival came to that home? Would the games on the iPad look the same? Would the interest be the same? Would the cartoons reflect a world that honors childhood innocence? Or would the Christian notion of “childhood” take root in the home?3 And what if the biblical narratives became a daily source of divine truth in the hearts and minds of the children? It might just be that they begin to ask deeper questions: “Mom, why does Wile E. Coyote never win?” or “Why did Nazi Germany think they could defeat Russia in winter? That was pretty dumb, huh?”

In this moment, we witness the transformation from passive consumption to active engagement, where curiosity, shaped by the knowledge of God, leads to deeper learning. Their hearts and minds begin to be formed by divine truth, and their learning becomes not just about gathering facts but about seeking the wisdom that fills in the gaps, the knowledge that leads to understanding, and ultimately, the encounter with the living God. Thus, John Milton (1608-1674) and his “Tractate on Education:”

“The end then of Learning is to repair the ruines of our first Parents by regaining to know God aright, and out of that knowledge to love him, to imitate him, to be like him, as we may the neerest by possessing our souls of true vertue, which being united to the heavenly grace of faith makes up the highest perfection.”

This kind of learning transforms us—when curiosity, driven by godliness, leads to personal application. In this process, we are drawn out of the shallow waters of information and into the depths of wisdom, where learning becomes an act of worship. The mother, no longer fighting against the tide of distractions, now shepherds her children toward a deeper engagement with the world. She invites them to seek and find, to ask and receive.

Here, in the sacred pursuit of learning, the Holy Spirit draws us into the fullness of who we are meant to be. Learning, in this sense, becomes an act of worship and discipleship. It moves us beyond the mere accumulation of facts to a place where we are transformed by the truth we encounter. We are reminded that God’s truth is not static or impersonal; it is dynamic, relational, and transformative. It calls us deeper—deeper into our relationship with God, deeper into the world He created, and deeper into who we are becoming in Christ.

The tired mother now becomes a guide, shepherding her children into the richness of curiosity shaped by divine truth. And in that moment, the tension between worldly distraction and godly engagement finds some resolution, not through force, but through the gentle power of a Bible story that captures the imagination and transforms the heart.

This happens when godliness fuels curiosity—when the pursuit of knowledge is not just an exercise in information-gathering but a journey toward becoming more fully alive, more fully human, as we live in the light of God’s eternal truth.

Ultimately, the holiness of deep learning is not just about what we know but about who we become in the process. It is about learning that moves us closer to God, closer to one another, and closer to the divine mystery that sustains all things. And this is the great promise of learning in the Christian life: as we grow in knowledge and wisdom, we are drawn ever deeper into the presence of the One who is Truth Himself.

And nothing is boring about that.

References

Augustine, Saint. The Confessions of St. Augustine. Translated by E. B. (Edward Bouverie) Pusey, 2002. https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/3296.

Frohnen, Bruce. “Edmund Burke & the American Revolution: The Whole Story,” April 11, 2016. https://theimaginativeconservative.org/2016/04/edmund-burke-and-the-american-revolution-the-whole-story.html.

Leslie, Ian. Curious: The Desire to Know and Why Your Future Depends On It. Basic Books, 2014.

Milton, John. “Of Education: Text.” The John Milton Reading Room at Dartmouth, from the 1644 Original 2014. https://milton.host.dartmouth.edu/reading_room/of_education/text.shtml.

Postman, Neil. The Disappearance of Childhood. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2011.

Taylor, Charles. A Secular Age. Harvard University Press, 2018.

Burke was a brilliant mind in an era of brilliant minds. His defense of American rights were summarized by Bruce Frohnen: “Throughout his writings on America Burke returns to his essential point: Britain and America both had prospered under a system of “wise and salutary neglect,” in which the colonies largely governed themselves internally, within the broad outlines of British tradition and the overall requirements of the British Empire. Parliamentary innovations, centered on direct taxation and a series of intrusive policies aimed at enforcing it, put Americans in rational fear of their accustomed rights. Given that America was a set of distant colonies that could not be made an integral part of British government, a policy of conciliation was best for all concerned.” Se Brucee Frohnen, “Edmund Burke & the American Revolution.” https://theimaginativeconservative.org/2016/04/edmund-burke-and-the-american-revolution-the-whole-story.html.

Augustine, The Confessions of St. Augustine, Book One, paragraph one. See https://faculty.georgetown.edu/jod/augustine/conf.pdf.

See Neil Postman, The Disappearance of Childhood.