The Public Theology of Lectio Sacra

On the Public Reading of the Scriptures, Illiteracy, and Sacred Elocution

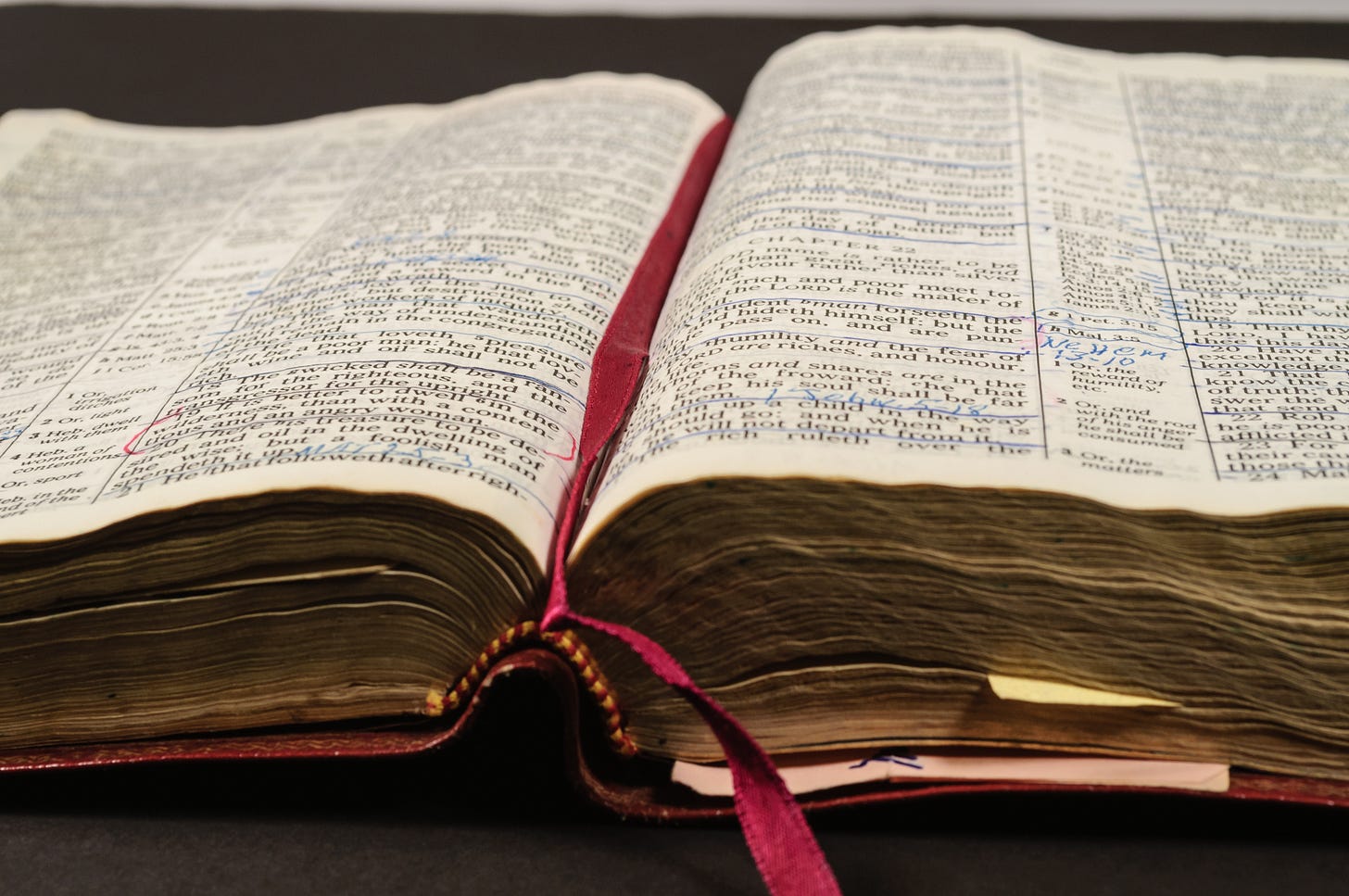

What is the relationship between sacred elocution and public literacy? Such a question, with its archaic content, demands that the author stand trial before the justified scoffer, “Why not tell the rest of us what ‘sacred elocution’ is, eh professor?” No. You are right. The phrase is obscure. So, let me start with some much-needed clarity. Sacred elocution is a subdivision of general elocution.

“Okay, smart aleck.”

You got me. Well, I do want to arrive at a definition of sacred elocution. I believe that learning sacred elocution is an essential part of the theological curriculum for the education and training of pastors. And, as I hope to convince you, the well-trained minister will have an effect on you, your children, and your grandchildren. I believe that Western Civilization is intrinsically tethered to sacred elocution. But before we go further, I want to consider a few biblical citations for it and then attend to sacred elocution’s most glorious setting for its practice. I think the definition will emerge in your mind as you read. Then, I will feel better about definitions and such.

Let’s start with Paul’s admonitions on sacred elocution.

The Apostle Paul and the Public Reading of Scripture

St. Paul wrote about the public reading of Scripture in several letters to early Christian communities. One of the most relevant passages can be found in 1 Thessalonians 5:27, where he wrote: “I charge you by the Lord that this epistle be read unto all the holy brethren.”

In this passage, St. Paul encourages the public reading of his letter to the Thessalonians, a common practice in early Christian communities. Public reading of Scripture (Lectio Sacra, the sacred reading) was a way for early Christians to hear and understand God’s word and to strengthen their faith. It still is.

In other letters, such as Colossians 4:16 and 1 Corinthians 14:26-40, St. Paul also emphasized the importance of orderly and edifying public speaking in the church, including the public reading of Scripture. In these passages, the great Apostle emphasized that speaking and singing in the church should be done with clarity and understanding to build up the church community.

I Timothy 4:13 in the English Standard Version (ESV) of the Holy Bible reads: “Until I come, devote yourself to the public reading of Scripture, to exhortation, to teaching.”

This verse is part of the first letter of St. Paul to Timothy, his disciple and co-worker in the ministry at Ephesus. The emphasis on preparing Timothy for primary duties in shepherding the flock of Jesus Christ has caused the Church to name 1 and 2 Timothy and Titus “the Pastoral Epistles.” Of all the things the Apostle could have told Timothy to study he stressed the public reading of scripture, preaching, and teaching. Every pastor should be well-versed—literally—in this section of Scripture.

Thus, St. Paul—viz., the Holy Spirit speaking through Paul—placed great importance on the public reading of Scripture in the early Christian church and encouraged its practice as a means of strengthening the faith of believers and building up the church. So, why wouldn’t we do the same?

Why would anyone disregard excellence in the public reading of Scripture?

Before answering that question, let’s admit the obvious: the public reading of the Word of God is reaching an all-time low in Western nations. I challenge you to do what I ask seminarians to do in my class on liturgy. Go to several local churches of different denominations, say, four local congregations of different historical branches of Christianity (e.g., Independent, i.e., unaffiliated; Baptist, Pentecostal, and Presbyterian or Anglican). You will undoubtedly come away with a variety of experiences of reading Scripture in the service. Generally speaking, those churches that follow and use a lectionary in worship (Lectio selecta) or practice a continual reading through a book of the Bible (Lectio continua) will have more public reading of the Bible. A lectionary is a one, two, or three-year plan of reading through the Scriptures, sometimes including an Old Testament and New Testament reading and, in other more traditional Protestant settings, an Old Testament, a Psalm, a New Testament Epistle, and a Gospel reading. The lectionary has its roots in rabbinical Judaism. Paul mentions this in Acts: “For from ancient generations Moses has had in every city those who proclaim him, for he is read every Sabbath in the synagogues” (Ac 15:21 ESV). The most famous instance of lectionary reading is when our Lord read from the prophets. That day, the selected passage was from Isaiah. There has never been and never will be a more stunning public reading of Scripture:

“And he came to Nazareth, where he had been brought up. And as was his custom, he went to the synagogue on the Sabbath day, and he stood up to read. And the scroll of the prophet Isaiah was given to him. He unrolled the scroll and found the place where it was written, ‘The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has anointed me To proclaim good news to the poor. He has sent me to proclaim liberty to the captives and recovering of sight to the blind, to set at liberty those who are oppressed, to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor.” And he rolled up the scroll and gave it back to the attendant and sat down. And the eyes of all in the synagogue were fixed on him. 21 And he began to say to them, “Today this Scripture has been fulfilled in your hearing” (Lk 4:16–21.).

In Lectio Selecta, lectionary reading, the reader, the preacher (those can be one and the same as in Jesus’ case), and the congregation can be most assured that the minister did not choose the passage for some personal goal or programmatic agenda. The practice of Lectio Sacra does not guarantee that the exposition of the Scripture will be faithful. Of course, Scripture can be read throughout the service, and the exposition is either missing or false. Public reading without faithful exposition is dangerous, to say the least. But so is denying the people of God the Bread of Life, plenty of it with its intrinsic variety and delivered with excellence forged by holy practice. On the other end of the spectrum, one may observe only a mite of sacred text in a service. For instance, the only public reading of Scripture in many Christian communities is a reading by the pastor before the sermon. Even that reading can be limited to a verse or two. Those are the polarized ends of the public reading of Scripture. Most congregations live in the middle regarding the public reading of the Bible. What did we do with all that time given to the reading of Scripture in the service? Limiting the public reading of Scripture creates an undeniable void of space, a vacuum made by a bad choice that is often filled with talk, special music, or long stretches of standing and reading lyrics from an overhead screen and mouthing or singing words to a melodic phrase that is known by only the initiated. As someone wrote some time ago, such a scene so common in (mostly Protestant) Christian communities across North America is more akin to pre-Reformational, and counter-Reformational congregations in Europe than to movements led by Calvin, Luther, or Wesley.

There could be several other reasons why a minister or church governing body might deemphasize excellence in the public reading of Scripture:

Emphasis on other aspects of worship:

Some people might place a higher priority on other elements of worship, such as music, and therefore give less emphasis to the public reading of Scripture. It is impossible to justify the position from the Scriptures, synagogue liturgy, the early Church practice, or the testimony of church history, yet it is so.

Lack of resources:

I read this one. I can’t believe it, but I have missed other things. Some Christian communities may say that they lack resources, such as trained readers, to achieve excellence in the public reading of Scripture. While Paul emphasized the care of the public reading of Scripture, he did not set an unachievable standard. If God commanded something to be done, God provided the ways and means. The education and training of pastors should provide the resident “subject-matter expert” in the public reading of the Scriptures. So, considering the present challenges in theological higher education, such a local church may have a valid point.

Changing attitudes towards worship:

Some communities may have adopted a more informal or contemporary style of worship, which may not place as much emphasis on “formal” aspects such as the public reading of Scripture. That is likely, the most likely cause for the disappearance of the public reading of Scripture. The case at hand begs the question: Did the dearth of the public reading of the Bible in worship create a more “casual” attitude towards divine services? Or did “casual” worship (an oxymoron) remove scripture reading? Does the deconstructed liturgy now suppress the public reading of Scripture? Going further, we might ask, has the diminishing voice of Scripture in our Christian communities spawned a lack of reverence in other areas of common life? There is a link here, and the repercussions are and will be devastating.

Different theological perspectives:

Some theological traditions may place less emphasis on the importance of the public reading of Scripture and instead emphasize other aspects of worship or religious practice. We ask again, “Where is the deemphasis of Scripture reading justified in Scripture?”

Declining literacy:

In some communities, declining literacy rates and a general lack of familiarity with the Bible may make the public reading of Scripture less relevant or meaningful. I fear that this is not only so but came about as a result of the failure of ministers to follow the “old paths” of Gospel liturgy and read plenty of scripture. I am not the only one concerned that we are seeing declining literacy rates because we are witnessing a disappearance of the public reading of Scripture from our churches. The Bible encourages literacy. Secularism discourages reading and elevates image. There is a catastrophic consequence of silencing the Word of God in public worship.

I want to say, “In summary, . . .” and be done with it. “In summary, these are just a few possible readings on the public reading of scripture is declining.” But the reasons for suppressing the public reading of Scripture are more sinister. The reasons are like the roots of poison trees growing in the dark moisture of the city sewer. The reasons reek of unhealthy consequences as much as contaminating causes. One thing is for certain: while the emphasis placed on the public reading of Scripture can depend on many factors, including cultural, historical, and theological context, the bottom-line responsibility lies at the feet of ministerial supervisors, educators (the Paul figure in the equation), and Christian shepherds (the Timothy figure). But we are told, “Attention span is shorter for most Westerners. Really? Folks can binge-watch six seasons of Russian novels made for television. Maybe we have an attention decision problem more than an attention deficit problem. I do not discount neurological cases of ADHD. I witnessed the disorder at work in my own life before the DSM gave the diagnosis a name. Yet, we don’t order the normal by the exceptional. The truth is, we are as capable as our grandparents to pay attention. What if the issue is giving our attention to the wrong things? And if so, have we been duped?

In summary, “Yes.”

What to do?

The ostensibly reasonable response to a need for more scripture read publicly is to write, “Pastors, start reading plenty of scripture in the public services of the Church. Fathers and mothers, consider it an urgent admonition to commence audible reading of scripture in your home posthaste.” But the reasoning of Man alone cannot create a desire to read the Word of God publicly. Only the Spirit of God can so transform the wills that we delight in doing God’s will. Grace empowers personal holiness and sets us free to follow the Lord in love. So the apparent response must recognize the actual power that is capable of awakening the dead to the law of God. And His law is our joy. So the answer to this, as with so many other problems in our churches and society, is spiritual. At this point in the secular age, the way to have more scripture read publicly (and enjoy its myriad benefits of human flourishing) is: We need revival. I know that is an oft-cited response to every ill of the contemporary Church. However, some things are repeated because they are true. Repetition of familiar phrases does not negate urgency nor diminish danger when one’s house is on fire. So, I say it again. We must have revival. Rather than point to the First or Second Great Awakenings, the Methodist revivals in England, or other similar spiritual awakenings, I point to an ancient case study that is remarkably close to ours. I am thinking of Josiah and the rediscovery of the Word in ruins. It happens to be a divinely inspired case study.

2 Chronicles 34:1-33 as the Frame for our Present Plight

This verse represents the vision for the renewal of the preeminence of the Word of God in Western Christianity:

While they were bringing out the money that had been brought into the house of the LORD, Hilkiah the priest found the Book of the Law of the LORD, given through Moses. Then Hilkiah answered and said to Shaphan the secretary, “I have found the Book of the Law in the house of the LORD” (2 Chronicles 34:14–15).

In the Chronicles of Israel, the Holy Spirit allowed the Church throughout time to consider the striking case of King Josiah of Judah (2 Chronicles 34). The boy-king had the heart of an ancient prophet. He was humiliated at the indignities of idolatry in Israel. Thus, in the eighth year of his reign (he was 16 years old), he sought God (v. 3). And in the twelfth year of his reign (at the age of 20), Josiah began to demolish the idols (Vv. 3-7). In the eighteenth year of Josiah’s rule, the devout young King began a revitalization of worship for Almighty God. So, he sent out officials, an ambassador (Shaphan), the mayor (Maaseiah), and the secretary, i.e., a clerk, or scrivener (Joahaz), to begin work on rebuilding the dilapidated temple (vv. 8-13). During the initial phases of the work, Hilkiah, the priest, discovers the “Book of the Law of the LORD given through Moses” (14). There is a disturbing and hopeful irony in the priest discovering the Word of God. The providential event merits its consideration. Back to the text. So, Shaphan, the scrivener, brings the Bible to King Josiah. The King ordered a public reading in his court. When Josiah heard the words of the law, he was greatly distressed and sought the counsel of the prophetess Huldah.

Huldah told Josiah that the Lord was angry with the people of Judah because of their idolatry and other sins but that he had heard Josiah’s humble and repentant heart. She prophesied that the Lord would not bring disaster during Josiah’s lifetime, but the judgment would come after his death.

Josiah then ordered the book of the law to be read—publicly—to all the people, and he led a reform movement in which he destroyed all the idols and idolatrous practices in the land. He also ordered the repair of the temple and the celebration of the Passover, as prescribed in the book of the law. The section of Scripture concludes with the blessings of restoring the Bible to its rightful place of prominence amongst the people: “And Josiah took away all the abominations from all the territory that belonged to the people of Israel, and made all who were present in Israel serve the Lord their God. All his days, they did not turn away from following the Lord, the God of their fathers” (34:33). “Josiah kept a Passover to the LORD in Jerusalem” (35:1).

This event is significant because it marks a turning point in the history of Judah and the revival of the worship of the Lord. Josiah’s discovery of the Scriptures and his response to them demonstrate the indispensable significance of the Word of God in shaping the lives of individuals and communities. In addition, the consequential episode is presented through the revival of the public reading of the Holy Scriptures. So, from this passage, we may assert that God blesses the restoration of His Word to its rightful place in the community. And what does the public reading of Scripture—with conviction and concern by the one reading it—bring to the people and their community?

The public reading of Scripture with concern brings conviction.

The public reading of Scripture with conviction brings repentance.

The public reading of Scripture with repentance brings transformation.

The public reading of Scripture with transformation brings a stay of judgment.

The public reading of Scripture with forgiveness brings renewed obedience.

The public reading of Scripture with obedience brings revival.

Sadly, many churches that pray for revival miss the biblical-historic and divinely revealed means of revival.

Excellence in All Things

In summary, the public reading of the Word of God by one who is under the conviction of the Lord, repentant before the Lord, transformed by God, shown mercy by God, seeks to obey God out of His mercy shown and has known the power of that process of revival in his life is, now, ready to “give attention” to the public reading of Scriptures. So, how about that? If we are so convicted and transformed, how should we approach reading the Word of God? Dr. D. James Kennedy used to stress “excellence in all things and all things for Christ.” Excellence is not in a dramatic reading, affective speech, for any supposed eloquence born of human intellect and ability. Rather, excellence in the public reading of Scripture is the attitude toward offering one’s best to convey the audible Word of the Lord to those in need. This is sacred elocution.

Elocution and Sacred Elocution

Elocution is the study of the art (and some say science) of public speaking, including the proper pronunciation, articulation, and delivery of a speech. Sacred elocution is a subset of general elocution that focuses on the art of public speaking in ecclesial contexts. There are, therefore, many similarities. There is one infinitely significant distinction.

The most critical difference between sacred elocution and elocution is subject. The Word of God dictates elocution and never the other way around. The tone and intention of the speaking should be different from general elocution. Reading the Holy Scriptures in the setting of worship is unlike a dramatic, casual, or news presentation. Neither preaching nor the public reading of the Bible is a conversation. The reading and preaching of the Word of God are part of a Word from Another World (Robert L. Reymond). Preaching the Word of God is not a monologue or speech, as may be given at a Rotary Club meeting. Sacred elocution emphasizes a solemn and reverent delivery, whereas general elocution may focus on a more varied range of speaking styles and techniques. In sacred elocution, the speaker aims to convey a sense of reverence and respect for the Word of the Lord being read, recited, or preached. In general elocution, the emphasis may be on other aspects such as persuasiveness, emotional impact, or clear communication.

The reading and preaching of the Word of God are supernatural elements in a Word from Another World.

In summary, sacred elocution in the Christian Church of our Lord Jesus Christ is a specialized form that focuses on the appropriate delivery of Scripture, while general elocution encompasses a wider range of public speaking skills and techniques. This, we can assert:

Sacred elocution is the art and science of speaking well in the preaching, teaching, and public reading of the Word of God.

Some variables of sacred elocution are present in general elocution but are always conditioned with this unvarying truth: the Bible governs sacred elocution. The solemnity and ethereal genesis of the sacred text necessarily constrain the speaker, reader, or preacher. This is an “alien voice” that originated in the mind of Almighty God. In this sense, the Bible is a Word from Another World. With that in mind, consider these six variables active in the reading and preaching of the Word of the Lord.

Sacred elocution is the art and science of speaking well in the preaching, teaching, and public reading of the Word of God.

1. Voicing (viz., Pronunciation):

The speaker should aim for clear and accurate pronunciation of biblical texts and words. What passes as acceptable in casual pronunciation (to “air” for “err” is historically incorrect; to “ur’ is the way to pronounce “err,” except when erroneous usage becomes convention, but that sends us back to the matter of illiteracy). Difficult Biblical names may have several pronunciations, particularly in the Old Testament. Biblical Hebrew should govern the pronunciation. Yet, one should always keep a general rule in mind: Let nothing in your person, speech, gestures, or attire distract attention from the Word of the Lord. Contextualization allows variance in the application of this principle. But the principle itself stands.

2. Velocity (i.e., Pace):

The speaker should control his speech’s pace to maintain the subject’s solemn and reverent nature. The reader or speaker employs velocity to mark the literary distinctions within the text, ensuring that such distinctions are made without imposing dramatic interpretations.

3. Volume (Proportion, i.e., control of the diaphragm pushing breath to amplify sound or reduce it)

The speaker should adjust the volume of his voice to suit the audience’s size and the space’s acoustics. Volume is not necessary to emphasize a phrase. Velocity and variation (changing the pace or inserting a pause) will delineate a change in the narrative of the text.

4. Value (Presence, i.e., emphasis):

The speaker should use emphasis to draw attention to important words and phrases in the text. Each of the variables of sacred elocution is interrelated and dependent on the other. For instance, value applied to a voice in the text can be achieved by variation.

5. Variation (e.g., pauses):

Variation includes (1) Pause. The speaker should use pauses to allow the audience to reflect on the message. Variation also concerns (2) Inflection: The speaker should use appropriate inflection to convey the meaning and emotion of the text.

6. Vectors (or, Particulars: coordinates that will influence the reading, e.g., posture, occasion, congregation, influencing factors like national emergencies, holidays, and the liturgical calendar):

The Reader or Preacher will take note of the vectors that influence the reading and reception of the Word of the Lord. For instance, reading on Christmas Eve, preaching at a graveside service of the death of a young person, or reading a Gospel selection on the First Sunday of Advent are all vectors to be considered in preparing to speak.

These six principles are meant to help speakers deliver the Word of the Lord in a way that conveys reverence and respect due to the divine subject and with the confidence of its innate power:

“So shall my word be that goes out from my mouth; it shall not return to me empty, but it shall accomplish that which I purpose, and shall succeed in the thing for which I sent it” (Isaiah 55:11).

Conclusion

All communication is, in the ultimate sense, “sacred.” For our Lord warned, “But I say to you that for every idle word men may speak, they will give account of it in the day of judgment. For by your words you will be justified, and by your words you will be condemned” (Matthew 12:36, 37 NKJV). Yet, as Paul urged Timothy, we who read and speak the Word of God publicly must give singular attention to the public reading of the Holy Scripture. This is not an option. Giving attention to Scripture reading and preaching is a ministry priority. For in the matter of pronouncing life and death, heaven and hell, and the will of God for human beings, such speech is different than any other form of speech and most certainly deserves our urgent attention and our utmost dedication.