The Prospect of Living in the Ordinary

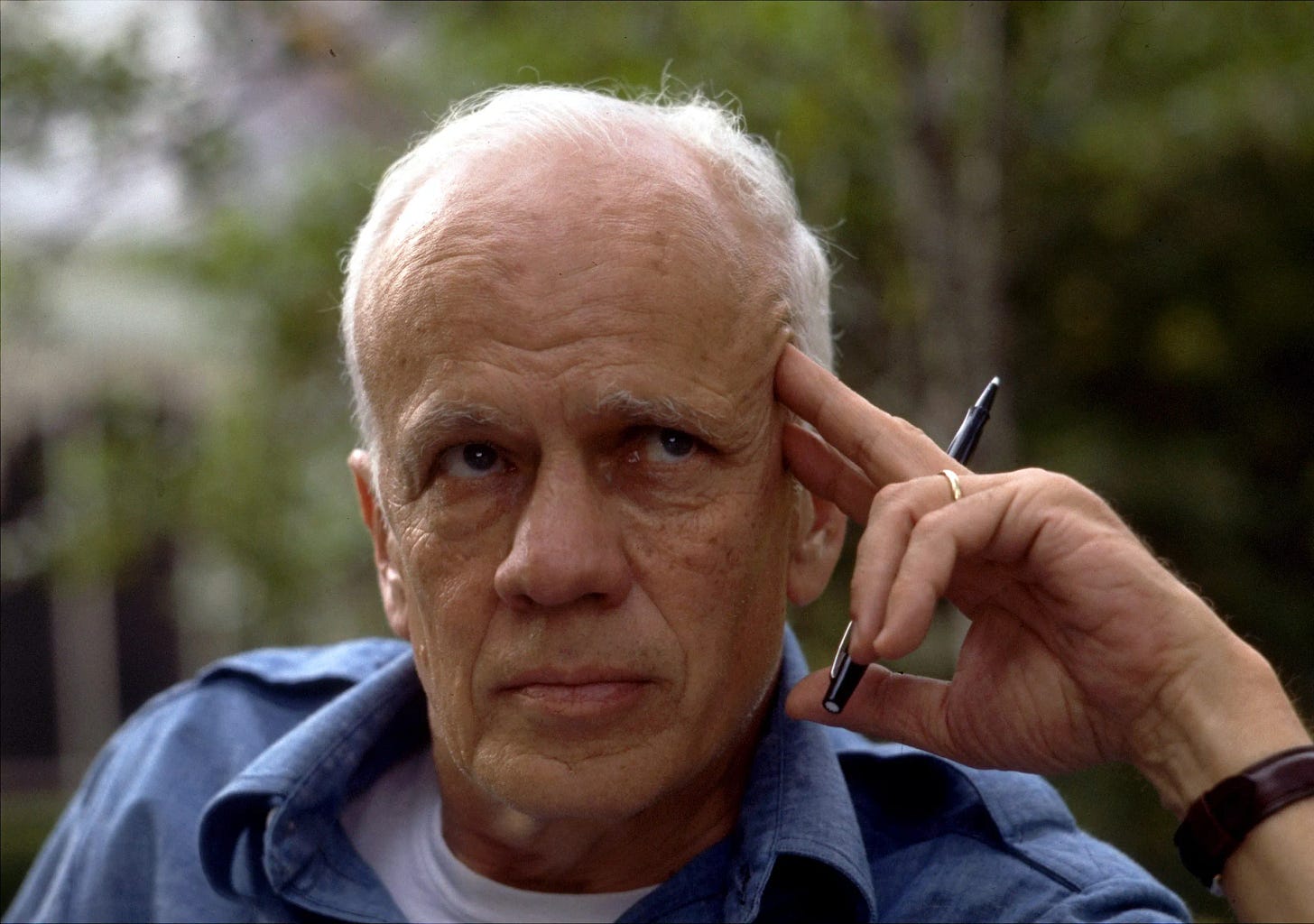

A Word for Christian Shepherds from the Fiction of Walker Percy

“Pastors should read deeply and widely,” I say to my students. So, as I surveyed my stack of recently read books, I noticed a glaring omission: no fiction. My son had recently scolded me half-jokingly over some blind-spotted personality quirk, “Dad, you need more novels in your life.” So, I turned to Percy—Walker Percy. I find comfort in either Flannery O’Connor or Percy. I read other fiction through the year, but when pressed I return to the familiar old places at Milledgeville or Covington.

It has done my spirit good to read Dr. Percy’s words again. I am not sure, though, when reading, whether I am the patient stretched out on Dr. Percy’s psychoanalytical couch or he is. I guess we both are, and that is his point. Well, then, I came across a line from Walker Percy in The Last Gentleman, Percy’s second novel, after The Moviegoer. It was very instructive for my ministry to read how Percy set up his main character, Will Barrett:

” It was not the prospect of the Last Day which depressed him but rather the prospect of living through an ordinary Wednesday morning.”

This single line made me put the book down. I considered and reconsidered the validity of his observation. I restated this as a premise for a fuller qualitative analysis (in my gray matter). Likewise, I remembered why it takes me so long to read Percy (and why I default to his cousin, Shelby Foote, to read historical prose). After chewing on this cud for a while, I began to see how very instructive Percy’s insight is for a Christian shepherd. When we preach and follow our Lord (and follow the follower, St. Paul) in His preaching, we learn to apply the theological truth to the existential. If we fail to make that necessary turn from concept to concrete, from theory to expression—or, if we turn too quickly, or if we swerve too abruptly—we lose a pastoral opportunity. To the degree that pastoral ministry is faithful to the Scriptures, losing opportunity can leave a congregation like cod on a black-sand beach, flailing fish in the shallows, gasping to breathe, and longing for the deep. Good Christian shepherding and the possibility of human flourishing are, indeed, related, if only by an unseen, mystical cord, or more simply, and, thus, more profoundly, a kind word of truth.

I find comfort in either Flannery O’Connor or Percy. I read other fiction through the year, but when pressed I return to the familiar old places at Milledgeville or Covington.

We remember, as N. V. Peal said in his Winning Friends, that a man’s toothache is of inestimable more importance to him than the reality of thousands of starving people in another land. And for many in our new Secular Age, as Charles Taylor labels it, making sense of living Percy’s “ordinary Wednesday morning” becomes an enormous psychological undertaking, which is to say an immense spiritual trial.

These are the days that we face. But they are our days, ours for the use: a gift of time from eternity. These are our lambs needing shepherding, His flock, really. Not ours after all. Reading Walker Percy has reminded me of the truth that the Psalms make so clear. But sometimes the wisdom and insight of another are necessary to help us see the obvious. So, yes, Son, you were right: I did need some more fiction in my reading to see reality clearer, and to diagnose the human condition better. Only then are we—I am—prepared to apply the appropriate Scriptural treatment to the pathologies of a human soul. Only then can I think of an ordinary Wednesday morning as the possibility of a lifetime.

References

Percy, Walker, The Last Gentleman. New York: Random, the Modern Library edition, 1997, 24.

Taylor, Charles. A Secular Age. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2007.