Shotguns and Biscuits

A night of near ruin and quiet redemption on the backroads of boyhood by Dr. Michael A. Milton

Some stories are too tangled in the kudzu of memory to ever be fully unraveled. This is one of them.

It involves my cousin Berlin and me—and a late-night encounter with a man who was, by local legend and whispered consensus, an accused murderer, a mean drunk, a petty thief, and, to crown the indictment, a serial polygamist who, by that time, was living with a woman of questionable character named Dolly. Her story—rich in its own tragic dignity—is a tale for another time. For now, let it suffice to say that the two of them shared a ramshackle cabin in the Piney Woods, and the prevailing rumor claimed that beneath that home lay the scattered remains of an unidentified IRS agent. Not metaphorically. The whispers said only parts of him were left. And, no, the meager tax debt to Uncle Sam was never collected.

“Everything I say is true—or could be true.”

— Jerry Clower

These are the stories that define a boy’s coming-of-age in the backwoods of Louisiana, where fact, fiction, and fear intertwine in equal measure.

A Campfire and a Departure

The night began innocently enough with a campout somewhere off Fore Road. The troop that evening included me, Berlin, his brother Ed, and a boy I’ll call “Sam”—Sam Taylor. Sam was a great friend but tended to be less inspired by the dangers we conjured up. In other words, you might say that he was sensible.

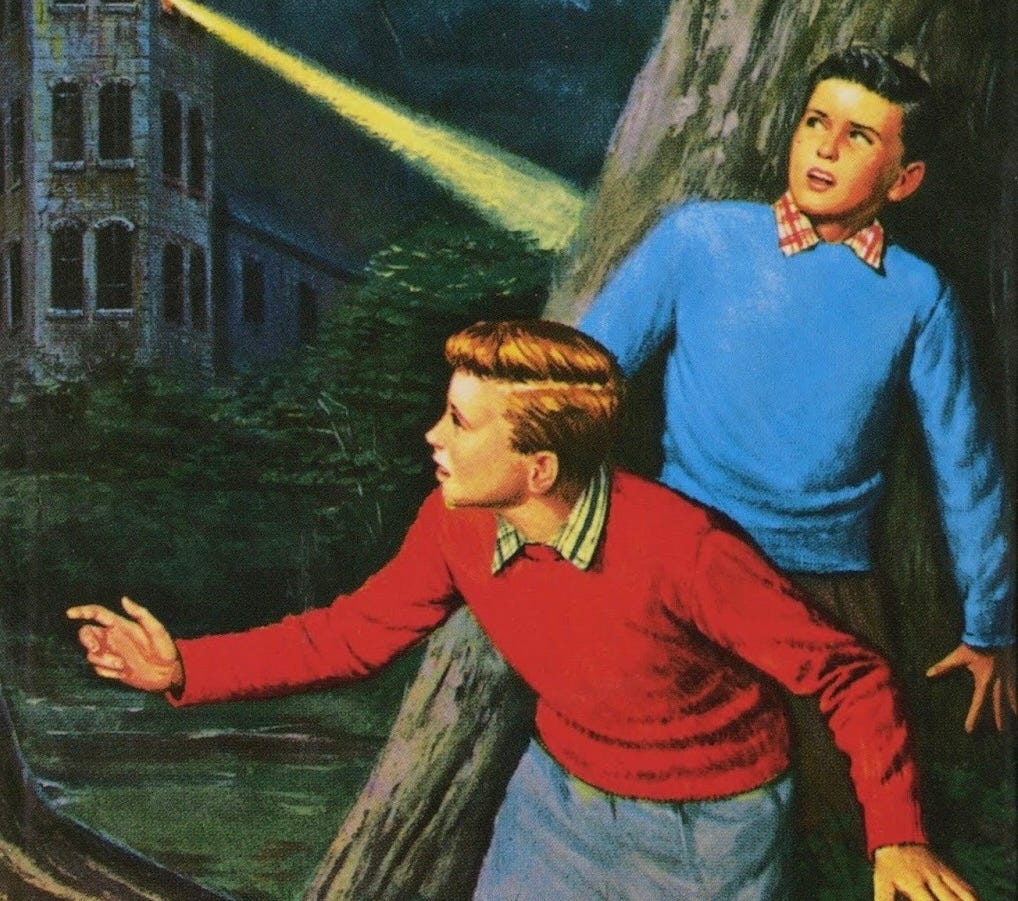

The sun hadn’t long gone down before we left our makeshift fire to pursue what we mistakenly called “adventure” and what our older selves would more likely call idiocy. We mounted our Western Auto “Western Flyers” bicycles and lit out into the sacred night. We were just like the Hardy Boys—except without the Midwestern charm, preppy clothes, engaging storylines, and intelligent faces.

We passed familiar landmarks—the fading shell of Archie’s Stand, where we used to collect superhero cards and waxy bottles filled with syrupy liquid (purchased from the sale of five-cent deposit Coca-Cola bottles)—and pushed on toward Springfield Road. We passed homes of cousins, kin, and double kin. As Berlin, my “double cousin,” once said, “The family tree in Livingston Parish looks like a Loblolly Pine—no limbs, just straight up.”

When we reached Berlin and Ed’s family home, Sam decided he’d had enough. He turned his bike toward home and pedaled off into the darkness. How many parents today would let their thirteen or fourteen-year-old son ride around at midnight for ten or more miles in the country? But that was normal then. The rest of us, however, thought it would be a grand thing to drag bales of hay into the road and watch what happened when cars came by. That’s what passed for fun. We never thought of danger. “It’s just hay.” At fourteen, boys feel invincible, and often think, if that's the word for their cognitive processes, as if they have at least ten years left before their brains catch up with the spit and vinegar inside them.

We hid in the ditch, suppressing laughter and waiting.

Enter Morgan Turner

The first car that came by was a sheriff’s vehicle. Of all the deputies in Livingston Parish, it had to be Morgan Turner.

He knew us by name. Had known us all our lives. We froze.

Morgan stopped his car, turned on the flashing lights, and stood there in the middle of Springfield Road like a lawman from one of those Burt Reynolds Southern-fried movies of the 1970s—hands on hips, sidearm at the ready, and his eyes narrowed. He tossed the hay bales into the ditch, nearly landing them on top of us.

“I know you boys are in there: Mike Milton, Ed, Berlin. I don’t care who the other one is. If I see y’all out again tonight, you’re spending the night in jail.”

He didn’t take us in. He was too tired. Said he’d speak to Mr. Billy and Aunt Eva. That threat was scarier than jail.

We took the hint. We changed plans.

A Misguided Visit

Sam—whose real name doesn’t matter here—had mentioned earlier that his little sister, Delilah Taylor, was staying in the camper parked out behind their house with some girls for a sleepover. But I already knew. Delilah had invited me to stop by. She and I had known each other since we were preschoolers, the kind of closeness that makes affection more familial than romantic. Though Sam’s little sister had made it clear she was agreeable to me properly pursuing her, I just couldn't see myself “kissing my sister!” (I don't have a sister—or a brother, for that matter, but that is how that felt to me). It just seemed unnatural. But I wasn’t riding seven miles at midnight through dark country roads to see Delilah.

No, my heart—such as it was at (thirteen), fourteen (fifteen, and sixteen)—was aimed squarely at Miss Barbie Bradington.

Barbie was a rare beauty and a quiet spirit: a rose of a girl with long brunette hair, a face that seemed lit from within, feminine wisdom, poised and polite, and an air of mystery that could stop a boy dead in his tracks—or make him pedal harder through the night. In other words, entirely out of my league.

So Berlin and I made our way to Sam’s house. I knocked on what I thought was his window, intending to rouse him quietly. It was not Sam’s window. It was his father’s.

The elder Taylor—wearing plaid pajamas and scowling in the porch light—was well acquainted with Aunt Eva and did not hesitate to invoke her name when issuing his threat. I had been with Mr. Taylor on all sorts of outings. I felt Mrs. Taylor wanted him to provide some fatherly guidance to me, which he certainly did. But tonight, he displayed a new attitude. I figured it out right away: he was not happy.

Inside the camper, I managed a glance through the little door. There she was: Barbie, radiant even in the blur of flashlight and fear. I connected for—about three seconds. The girls screamed as if a bobcat had pawed at the latch, and I mortified, backed away. This triggered even greater rage in Mr. Taylor. You see, I had thought maybe we were to leave after we visited for a while. What a stupid assumption.

There was no great romantic moment. Heck, there was no moment. There was only confusion, embarrassment, and the sound of a grown man telling two wayward boys to get on their bicycles, pedal off into the pitch black, and “do not come back.” Mr. Taylor’s son, our Sam, did not come out. He slept through our midnight visitation and summons before the High Sheriff of Taylorville. Sam later admitted that he hated missing the whole wrathful judging part.

It took us an hour to pedal there, and we left in less than five minutes. One might have expected a better reception for poor lads on a ten-mile bike ride at one a.m. to visit a gaggle of girls in a camper outside of Mr. Taylor's door. Others may say we were really stupid.

And so we left—another failed chapter in a long, strange night. But there was more.

The Return: Feral Dogs and Familiar Fears

We turned toward home. It was past one o’clock in the morning, the air thick with heat, humidity, and memory. That rough stretch of the Fore Road was our trial: broken houses, feral cats prowling like saber-tooths, Mastiff-like dogs that had never known a leash, and 1920s-era wringer washing machines on collapsing front porches—the moonlight danced on the corroded lead-white sheet metal, providing the only light available. Past those shacks, past fields of Brahman cattle (we called ‘em “Bremmer” cows, a Breemer bull has a hump on his back and meanness in his soul), and towards the little rough-hewn Tabernacle church built by disgruntled Baptists and Methodists,—we were nearly safe.

And then we heard it: the clatter of an old truck. Berlin didn’t need to say it. We both knew.

“Meb Graham,” he muttered.

Melvin “Meb” Graham was a nasty one, alright. Think Earnest T. Bass on Jim Beam with an attitude—and a string of charges from manslaughter to stealing cows. In reviewing this little story, Berlin told me that he remembered Meb Graham as having more arms than teeth. That is a vividly accurate and unnecessary memory.

The inebriated, geriatric Chevrolet truck wheezed beside us, drawing a breath like an asthmatic hound. In the cab: a filthy younger man at the wheel, Dixie beer in hand, Camel cigarette drooping from his mouth. We didn't know him, but he was the protégé to the master seated in the passenger seat. In the passenger seat: Meb, wide-eyed, unwashed, whisky-drunk, and angry. A rack of guns gleamed behind them, the only clean things in that cab.

“Who are you boys? I can't see ye,” he barked.

Berlin, ever honest, said, “Berlin Coxe and Mike Milton.”

I shot him a look. “Berlin,” I whispered a brotherly rebuke, “don’t tell them anything else.”

But he did. I can’t blame him. They were moving at the speed of our walking, right beside us, jalopy sputtering every inch of the way. Intimidating. Mercifully, the leaking gasoline overcame the other fumes from within that truck. Ugly. Stinkin’. Mean.

So, Berlin said we were “going to Aunt Eva’s.” Her old house was, indeed, our destination, our sanctuary, but old Meb knew every house. When he heard “Aunt Eva,” it was like giving him a GPS location pin.

So what was up with Meb? He had a theory. Someone had been tapping on Dolly’s window. He was convinced it was us. He proclaimed that he now had the culprits.

“No, sir,” Berlin said. “We haven’t been anywhere near there.”

“You lying no good . . .” Meb started cursing. And then he reached behind him and pulled out a shotgun.

The Dash to Grace

I was looking leftward toward a pasture. “Berlin,” I whispered. “When I say go, you run with me over the fence and across that pasture.”

I knew the way: the Fore Farm, the old fields, the fence. I had run them a thousand times. There were only docile “White Face” Herefords in there. No Bremmers. We could do this.

The truck coughed, sputtered, and died.

“Now!” We bolted.

Meb was hollerin’. The maniacal sidekick gave a Rebel yell to encourage the dogs: “Get ‘em! Get ‘em!” Cats were screaming and dogs were howling. The demonic cacophony echoed across the thick air like an eight-party phone line on a Friday night. The two backwoodsmen gave chase on foot, then not at all. We could hear Meb coughing up his whiskey, Dolly’s cheap perfume, and camel cigarettes, even as we sprinted through open fields, past Uncle Pepper’s old house, over barbed wire and black soil, down cornfield rows, across turnip patches, and past Confederate ghosts, until we reached Aunt Eva’s.

We said not a word as we entered that old Civil War-era house from the back porch. You could still smell the cypress logs dragged by mules from the Amite River. We collapsed in my little bedroom, a little bigger than most closets today. I inhaled the breeze through the open window, which brought the pungent comfort of chicken coops and sun-warmed feed that cooked in the day and cooled at night. The smell of money, they used to say. That night, it smelled like deliverance.

Biscuits and Mercy

At dawn, Aunt Eva was in the kitchen. The scent of biscuits and butter, coffee and fig preserves—these were consecrated sacraments to those Southern boys. We followed the scent like devoted pilgrims—drawn by the aroma of breakfast simmered in cast iron. The pink linoleum table seemed more sacred than sparse now, a kind of altar for two weary prodigals who had nearly met their end. The linoleum table was brought in after WWI but didn’t make it out of the Truman years unscathed. It had a pretty good-sized crack in the middle that Aunt Eva covered with a vase.

There were no lectures. No interrogations. Just Aunt Eva sliding plates across the table, and that look she gave—half suspicion, half mercy.

“Well, boys,” she said, “how was the campout?”

Another judicial hearing.

Berlin froze, fork suspended midair. I looked over at him and knew he was weighing truth against self-preservation. He blinked once, slowly.

I cleared my throat, but I continued to fiddle with the plate as if I were completely absorbed in cutting bacon, which I usually would have eaten like a stick of candy. I couldn’t look her in the eyes. “Well, it was a whole lot of fun, Aunt Eva. A whole lot.”

Berlin squinted at me like I’d lost my mind. I gave a quick nod toward his plate. “Just keep eating.”

We did.

And maybe that’s where the gospel was clearest that day. Not in any words we said, or even in the silence that followed, but in those biscuits—split open, steaming, slathered with fig preserves she’d canned herself. Each bite was undeserved. Each moment, a kind of mercy. The threat of imprisonment, the long journey in the dark, lost opportunities, lost love, and maniacal villains complete with the soundtrack of killer cats and rabid dogs now faded into the past like it had never happened. Maybe that's what heaven is. The bad stuff never happened. Just hot biscuits and butter. And fig preserves.

Aunt Eva turned on the old Zenith radio, but the morning agricultural report was barely comprehensible due to the static from a station in Mississippi.

We should’ve been in jail. Or worse.

But we were here, seated, safe, and fed.

The radio finally picked up a signal, “It’s gonna be real hot today, folks,” said a deep baritone drawl voice coming in from Amite County.

“Aunt Eva, can I get another biscuit?” I looked at Berlin. He had eaten about four catheads, and now he wanted more? After what we went through? But my little cousin was content and happy. Aunt Eva had her back to us. I wasn’t sure if she was chuckling or just foolin’ with the radio dial.

“You mean, ‘May I?’”

“Yessum.”

“Why sure, Berlin. Coming right up, son.”

That’s how grace finds us sometimes—at a pink kitchen table in the aftermath of folly, with just enough goodness to make you wonder why you were spared, and enough mystery to know you didn’t spare yourself.

And there will be people from your childhood who say, "How did that kid who couldn't steer clear of trouble if it were a mile away end up as a full bird colonel and seminary president!"

Great reading, Dr. Milton.