When I read to be reminded of the human condition and to be revived by the hope of a benevolent God, I turn to Percy—Walker Percy. Indeed, I find insight and comfort in either Flannery O’Connor or Walker Percy. I read other fiction through the year, but when pressed I return to the familiar old places at Milledgeville or Covington.

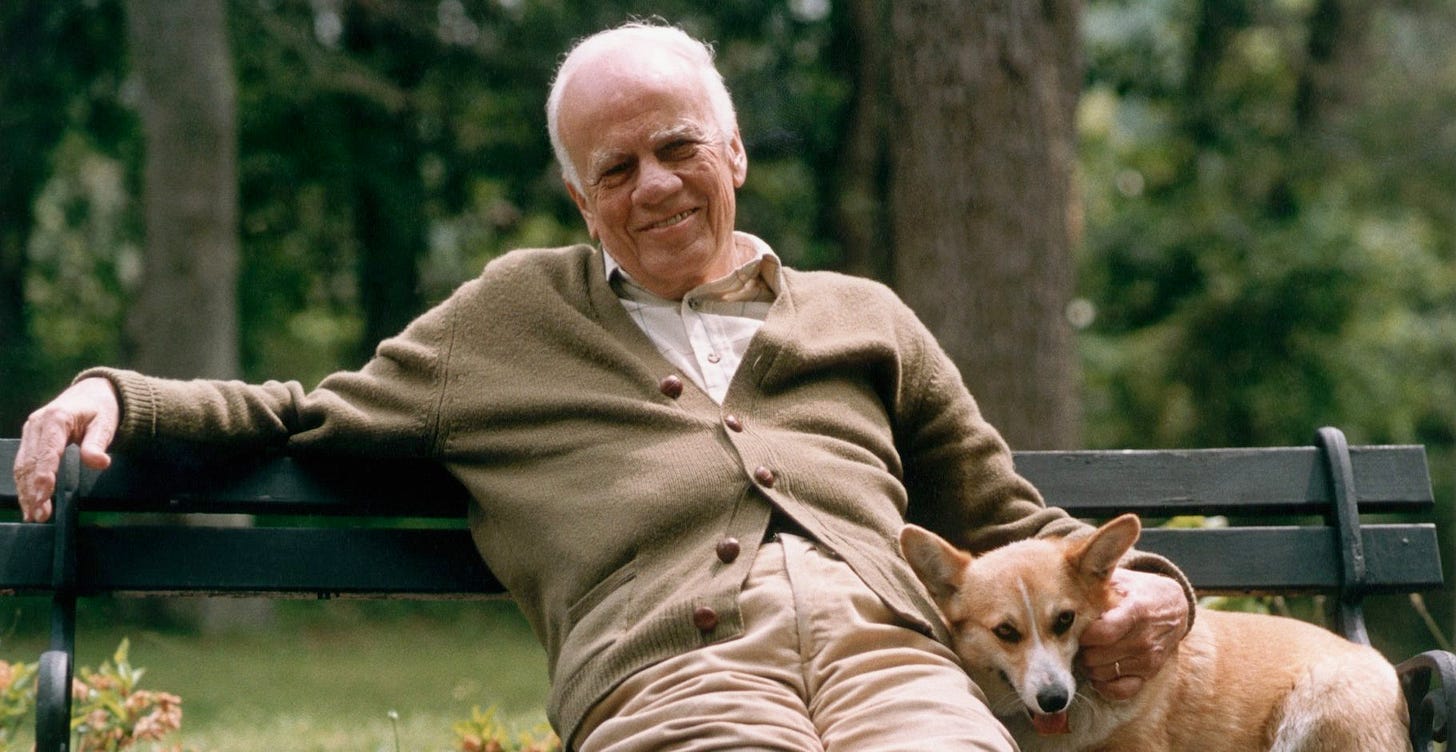

Walker Percy was an agnostic converted to Christianity. He was a physician educated at UNC-Chapel Hill and Columbia School of Medicine. A severe battle with tuberculosis ended his medical career in psychiatry (my father became friends with Percy through that medical connection). Percy’s forced change-of-career turned out to be a gift for the rest of us. His writing reflects both his insights as a psychiatrist and, greater still, his Christian worldview: creation, fall, redemption, consummation. I recently read Dr. Percy’s words again. I am not sure, though, when reading, whether I am the patient stretched out on Dr. Percy’s literary psychoanalytical couch or he is. I guess we both are, and that is his point. I came across a line from Walker Percy in The Last Gentleman, Percy’s second novel, after The Moviegoer. It was very instructive to read how Percy set up his main character, Will Barrett:

“It was not the prospect of the Last Day which depressed him but rather the prospect of living through an ordinary Wednesday morning.”

This single line made me pause. I put the book on the end table next to my bed. I stretched my heads to place them, fingers clasped, behind my head. Propped up for serious cogitation, I stared at the ceiling fan overhead. I considered and reconsidered the validity of Percy’s observation. I restated this as a premise for a fuller qualitative analysis (in my humble gray matter). Likewise, I remembered why it takes me so long to read Percy (and why I default to his cousin, Shelby Foote, to read historical prose). After chewing on this cud for a while, I began to see how very instructive Percy’s insight is for a Christian shepherd (I am a pastor, a physician of the soul, if you will, also grounded by an infectious disease from an African mission). When we preach and follow our Lord (and follow His follower, St. Paul) in His preaching, we learn to apply the theological truth to the existential. If we fail to make that necessary turn from concept to concrete, from theory to expression—or, if we turn too quickly, or if we swerve too abruptly—we lose a pastoral opportunity. To the degree that pastoral ministry is faithful to the Scriptures, losing opportunity can leave a congregation like a cod on a black-sand beach: a flailing fish trapped in the shallows, gasping to breathe, and longing for the deep. Good Christian shepherding and the possibility of human flourishing are, indeed, related, if only by an unseen, mystical cord, or more simply, and, thus, more profoundly, a kind word of truth.

Reading Walker Percy has reminded me of the truth that the Scriptures make so clear: We must be about "Redeeming the time, because the days are evil” (Ephesians 5:16). But sometimes the wisdom and insight of another are necessary to help us see the obvious.

—M. A. Milton

We remember, as N. V. Peal said in his Winning Friends, that a man’s toothache is of inestimable more importance to him than the reality of thousands of starving people in another land. And for many in our new Secular Age, as Charles Taylor labels it, making sense of living Percy’s “ordinary Wednesday morning” becomes an enormous psychological undertaking, which is to say an immense spiritual trial. Men dressed as women, mass murderers lauded as misunderstood saviors of transgenderism, demonizing good to exalt evil, exchanging the gold standard of Western Civilization and Judaeo-Christianity for bubblegum cards of postmodernity, open borders and Chinese spy balloons, and shutting down good-paying oil field jobs in America for lithium-hungry EV-battery rocks mined by slaves in China. The daily details of our time can form a litany of perilous nonsense recited in unison by the apathetic and the pessimistic. Surely, these are the kinds of daily challenges that Walker Percy meant but could never foresee. It’s just too crazy to believe, much less live through.

The daily details of our time can form a litany of perilous nonsense recited in unison by the apathetic and the pessimistic. — M. A. Milton

These are the days that we face. But lest we despair, they are our days, ours for the use, or waste: a gift of time from eternity. Pastors (and parents): These are our lambs who need shepherding, His flock, really. Not ours after all. Reading Walker Percy has reminded me of the truth that the Scriptures make so clear: We must be about "Redeeming the time, because the days are evil” (Ephesians 5:16). But sometimes the wisdom and insight of another are necessary to help us see the obvious. Only then are we—I am—prepared to apply the appropriate Scriptural treatment to the pathologies of a human soul. Only then can I think of an ordinary Wednesday morning as the possibility of a lifetime.

References

Percy, Walker, The Last Gentleman. New York: Random, the Modern Library edition, 1997, 24.

Taylor, Charles. A Secular Age. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007.