Michel Foucault (1926-1984) and the Ideas that Kill the Soul and Destroy Civilizations

The Dangerous Dreams of the Deconstructionists

I never met Michel Foucault, but I know him. And you know him too. His ideas are now influencing Western culture as much as anyone and more than most. A French social theorist-historian, essayist, and philosophical father of the deconstructionist movement (a term he did not like—sorry), the force of his writings, perhaps more than any other, became Postmodernism.

Reading his The History of Madness this week, as I prepared for a lecture on Foucault and Postmodernism, I encountered the writings of some of Foucault’s other disciples, like the feminist Dr. Judith Butler of the University of California at Berkley. She is one of many who continue to stoke the legacy of Foucault.

To read Foucault is to observe the mighty Mississippi at its head. Postmodernism is the mouth of the great river of ideas that reach back to trickles of the dirty water in the springs of Enlightenment, in Immanuel Kant and Frederich Wilhelm Nietzsche. But at its mouth, the philosophy opens up into a recognizable, single waterway of ideas in Foucault. There are currents, terrible and strong undertow, in the river of ideas: language as the primary truth (since the truth is, as Nietzsche wrote, merely “a mobile army of metaphors”), suspicion of the intellectual heritage of Western Civilization, rejection of even beneficent hegemonies in the community of nations, criticism of all Western institutions, a veritable stripping of the altar of Western religious values, and unleashing the most radical anarchist spirit of the French Revolution (“off with the king’s head”) to every authority. In Foucault, there is an immodest worship of unbridled hedonism, an unending pursuit of self-gratification, while questioning rational norms of reality that might inhibit self-actualization (e.g., gender as a social construct). In reading the essays of this unquestionably brilliant fellow, whose intellect and life was employed in the service of the anarchy of ideas, I recognize the “spirit of this present evil age” (St. Paul, Galatians 1:5). The works of Michele Foucault are the writings of a man whose life personified Romans chapter one (1:18-32), the teaching concerning the rejection of God and consequent downward spiral (to include working for the codification of his anarchy). The residue of his once prodigious pen still unleashes the spirit of “the man of lawlessness” (2 Thessalonians 2:7). As I read Foucault in preparation for my course on world religions and apologetics, I tell you the truth: I sensed a sudden, horrible rush of an icy bluster against my soul. It is a chilling wind of Adam’s insurrection, and a residual presence in the baser part of my soul, reminding me of my dark existential quest in the far-away past days of adolescence. This prodigal pathway led (and always leads) to sorrow. I hate it.

For though we walk in the flesh, we are not waging war according to the flesh. For the weapons of our warfare are not of the flesh but have divine power to destroy strongholds. We destroy arguments and every lofty opinion raised against the knowledge of God and take every thought captive to obey Christ (2 Cor. 10:3-5).

This week, I sought to teach our students to recognize this unique, now ubiquitous, philosophical voice in the music we hear, the literature we read, and the political philosophies we endure from elected leaders. It is there; there in the engrafted flesh of culture like a menacing virus. But we do not lament without hope for a cure. We who love God and love those infected by the virus—and we are all sinners—want to identify the ideas, “run to the fight,” not away from it. Our calling is to take Foucault’s thoughts captive for Jesus Christ, exposing them not merely for their ways’ blazing hellishness but also for their inevitable end’s invariable hellishness (2 Corinthians 10:3-5). For as Nietzsche went mad, as Foucault explored his pleasures with unbridled immorality, dying of disease from his illicit quest, so, too, all who deny God meet such nightmarish endings, whether in this life or the next. I would write with Jeremiah’s tears at this stage of Jerusalem’s fall, not his judgment.

Yet our Lord Jesus Christ stands over the crumbling idols of the imaginations of Foucault and Nietzsche in the bleak Postmodern landscape. Jesus, our Lord, and God offers redemption from the brutal totalitarian reign of sin; salvation from self. Jesus’ word comes not to the crowds as an angry mockery of the rebellion of little Man in his imaginary world without God but rather as a peaceful whisper in the deep, untouched places of the souls of a few who are not yet drowned in the river: He is there. His quiet voice of hope is heard, still, by any who would listen: “I am the way, the truth, and the life” (John 14:6).

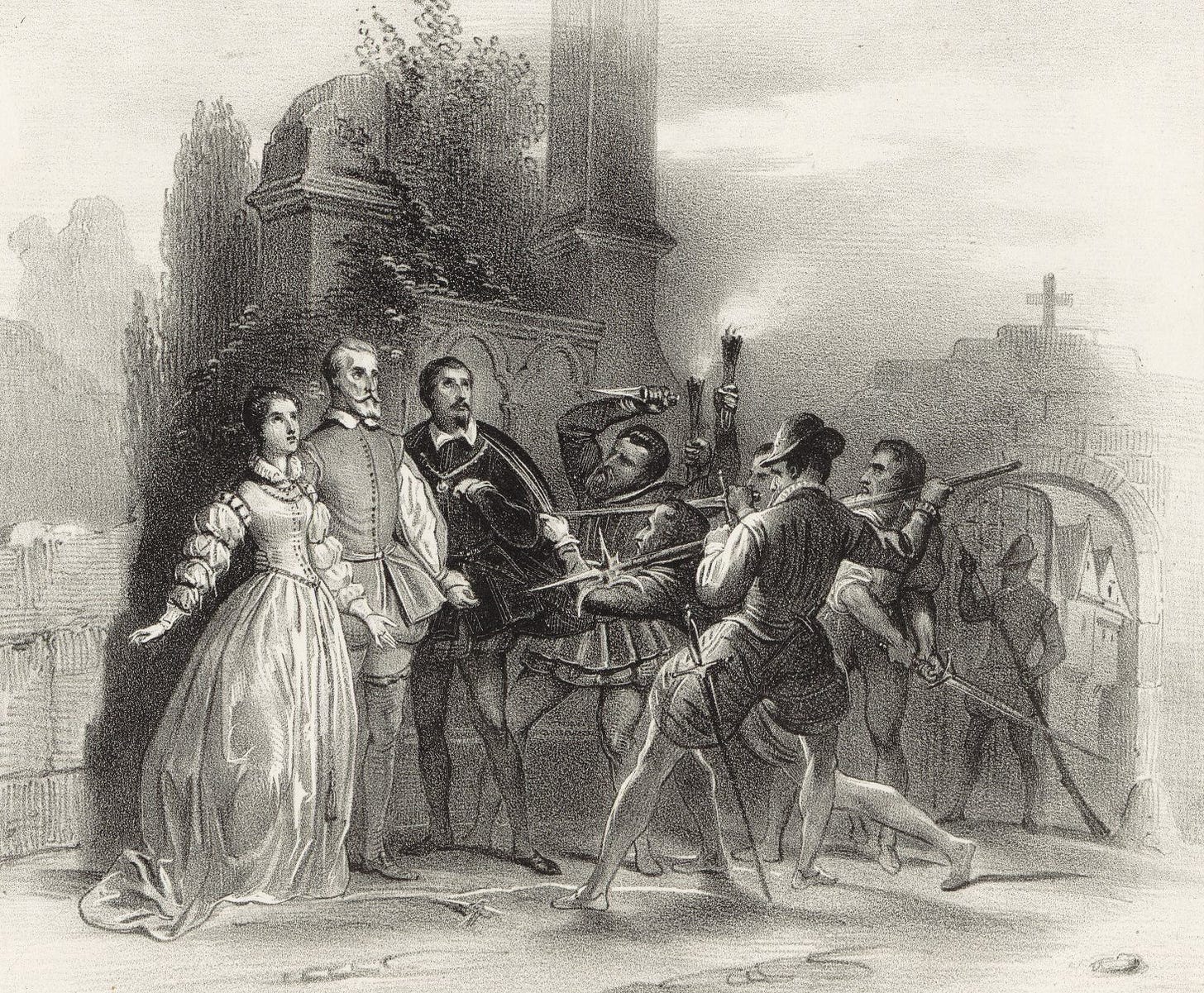

Foucault was a public intellectual who used his considerable abilities to assail the restraining powers that guarded the citadel of our society. True to the worst characteristics of his Gaulish ancestry, the little revolutionary then led each kingly virtue to a public guillotine. Foucault hunted down any vestiges of Christian values that remained and slayed them like Huguenot believers at the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre (Paris, 1572).

Yet the ablest deconstructionist can not utterly deconstruct the laws of God. The sacred Text has meaning. The meaning became incarnate in Jesus Christ. Reality will always survive the assault on properly fundamental beliefs. The sense of the transcendent in the human breast resists the alien and the pretender. God will not be mocked. And the purity of God’s love remains challenged but unmoved.